One of the main issues with russian long-range, jet-powered drones, such as the Geran-4 and Geran-5, is that they are much closer to cruise missiles than to conventional UAVs. Due to their speed, they may be out of reach of Ukrainian anti-aircraft drones and mobile fire groups armed with machine guns.

In other words, maintaining effective destruction of russian Geran-4 and Geran-5 requires the use of missiles. This effort is hampered by an obvious shortage of such weapons, which is difficult to overcome given the global scarcity of anti‑aircraft missiles, their extremely high cost, limited solid‑fuel production, and the expense of their guidance systems.

Read more: How China Could Gain Critical Edge by 3D-Printing Jet Engines for Cruise Missiles, UAVs

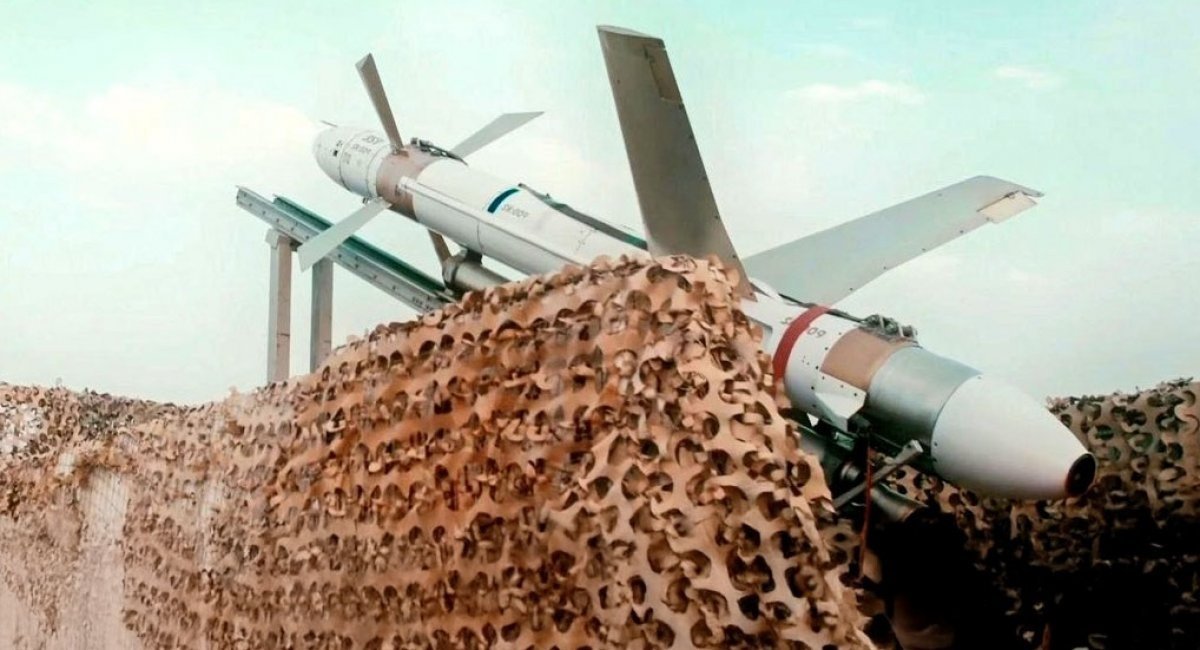

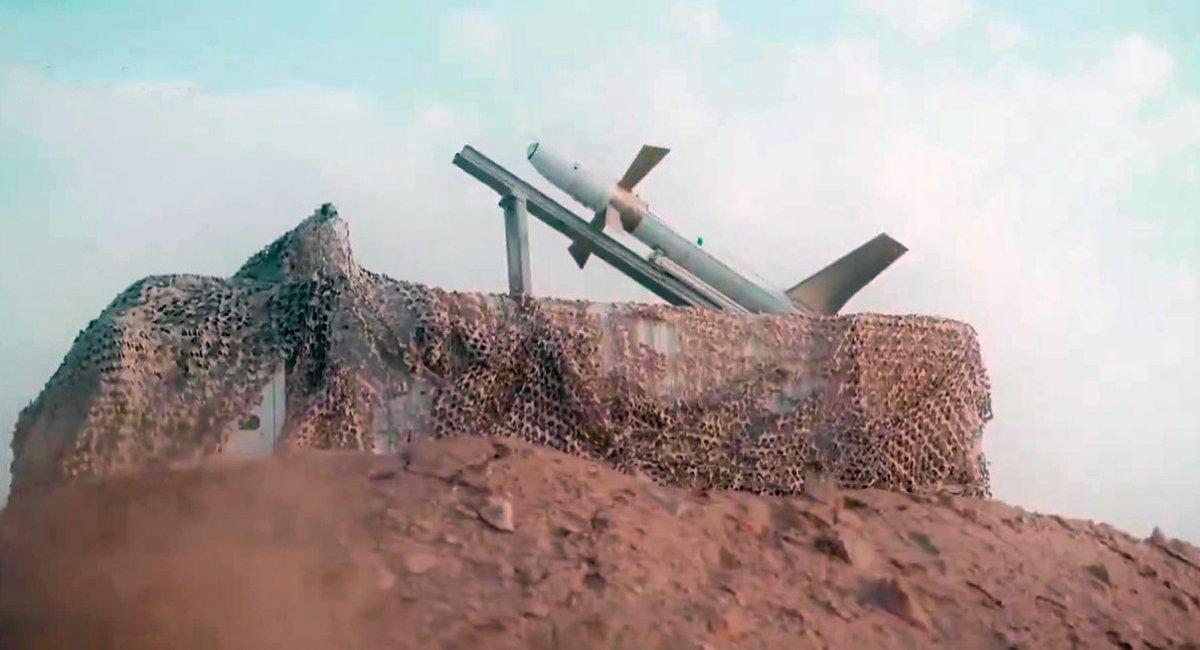

Therefore, if russia is actively using Iranian long-range weapons, it is worth mentioning Iran's specific means of destroying air targets. Specifically, the missile designated 358 and its updated, slightly simplified version, 359, are of particular interest. Both have the same canard wing configuration, as on the Soviet R-27 air-to-air missile, as well as large X-shaped wings.

Unlike the 358, which employed a sophisticated laser and optical sensor system to detonate its warhead, the slightly larger 359 operates without these sensors. It should be noted that the use of these missiles has been credited with the downing of a significant number of RQ-1, RQ-9, and Hermes 900 reconnaissance UAVs over Yemen and Israel.

The main conceptual difference between them and conventional anti-aircraft missiles is the use of a small turbojet engine instead of a solid-propellant one. This provides subsonic flight speeds of up to 600–800 km/h, while traditional solid‑fuel anti‑aircraft missiles accelerate to speeds of several Mach. Although the missile still requires a solid‑rocket booster, it can be simpler and is not constrained by the dimensions of the missile's fuselage.

The second and even more important feature is the rejection of traditional targeting systems. Instead of seeker or command guidance, a thermal imaging camera and direct operator control with additional integration of machine vision are used. In fact, the Iranian 358 and 359 missiles are anti-aircraft jet-powered drones.

In general, this critically distinguishes the method of using these missiles from traditional ones. They are launched from simplified launchers and loiter at a specified altitude over a designated area while awaiting a target. Once a target enters the engagement area, the operator assumes control of the missile and conducts the attack. Thanks to the use of a turbojet engine, the operator can adjust the thrust to a comfortable level, which is impossible with traditional solid‑propellant anti-aircraft missiles.

Another potential modification would be the integration of a parachute system, enabling recovery and reuse of the missile, or at least of key components, should it exhaust its fuel before reaching the target.

It should also be noted that Ukraine currently possesses only one of the two key components: proven control and guidance solutions used in anti‑aircraft drones. However, replicating this Iranian air target destruction system requires a stable source of cheap and mass-produced small turbojet engines.

If launched from an air platform, such as a light aircraft or a sufficiently large UAV, the missile would not require a booster. However, without a booster, it would be difficult to equip mobile fire groups with such a hypothetical weapon.

It is also worth adding that the Iranians have already offered their 358 anti-aircraft missile to russians. That was in 2023, but russians were not interested. One possible explanation is that the russian federation did not, and still does not, suffer from a critical shortage of conventional anti‑aircraft missiles.

Read more: From MQM-107 to Karrar to Geran-5: the Real Origins of russia's New Drone