European logistics remain poorly suited for the rapid redeployment of heavy units between fronts, meaning that moving equipment from Western Europe to the east can take weeks or even months. The bottleneck lies in the condition and capacity of key bridges and tunnels along strategic routes.

"We have old bridges that need to be modernized, narrow bridges that need to be widened, and non-existent bridges that need to be built," said European Commissioner for Transport Apostolos Tzitzikostas in a recent interview with the Financial Times, as quoted by Defense Romania.

Read more: Romanian Railway Problem Can Paralyze All of NATO Logistics

The European Commission has prepared a €17 billion investment plan to enhance military mobility, targeting 500 priority infrastructure projects for modernization between 2028 and 2034.

On a note from Defense Express, while Europe has a well-developed civilian transport network, certain choke points — such as old bridges or tunnels — remain unsuited for oversized or heavy military loads. Furthermore, many such locations could be easily paralyzed by long-range strikes in wartime.

The issue extends beyond railways to road transport as well. Moving heavy armor by wheels is slow, expensive, and requires significant capacity: relocating a battalion of CV90 infantry fighting vehicles would take at least 50–60 lowboy trucks.

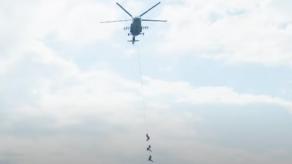

Ordinarily, airlift would be the best way to quickly transport heavy equipment over long distances, but European capability here is falling short of expectations. The available options are the A400M (37-ton payload), the C-17 Globemaster III (77 tons), and Ukraine’s An-124 Ruslan (120–150 tons). Of these, only the C-17 and An-124 can carry main battle tanks weighing up to 70 tons on average.

The A400M, while impressive in number, struggles even with IFVs in terms of capacity. For example, transporting one Puma IFV would take four days and two aircraft — one for the vehicle itself, and the second for the additional armor stripped off the Puma before loading.

Yet Europe has just eight C-17s in total, all in British service, plus 5–6 Ukrainian An-124s, which is far too few to deploy large formations quickly. U.S. Air Force cargo planes stationed in Europe could help, but only if not tied up by American operational needs, so the Europeans need their own fleet nonetheless.

Sea transportation offers another option: cargo ships and landing craft are effective and reliable for bulk transport, but their slow speed and exposure in contested waters pose serious risks. Especially in the Baltic and North Seas, where russian submarines and sea mines would likely be active.

In a potential open conflict with russia, low deployment speed of allied forces from Western Europe puts eastern nations (the Baltic states, for example) under great threat and give russia a dangerous window of opportunity to advance deep into allied territory before reinforcements could arrive.

Thus, Europe must not only ramp up weapons production, like Germany is doing, but also invest heavily in transport infrastructure modernization to ensure those forces and systems can be deployed rapidly. Importantly, though, Europe is fully aware of the problem, as indicated by recent funding commitments and statements by high-level officials.

Read more: Can NATO Defend Europe Without the U.S.? What the Alliance Still Lacks to Stand Up to russia