Some US-provided portable weapons captured by russian forces have been sent to iran, CNN reports. These include Javelin anti-tank and Stinger anti-aircraft missiles that were taken as trophies by russians as they took over Ukrainian positions.

According to the report, Ukraine keeps track of such occasions and informs the United States when it happens. Although the US official "don't believe that the issue is widespread or systematic." Still, CNN wondered if it may become a problem in the future, since iran can reverse-engineer these US weapons like it managed to do in the past.

Read more: Based on Ukrainian Military’s Experience, the US Army is Experimenting With Dropping Grenades from Drones, China Begin Production of ‘Flying’ Mortars

For example, the media says, the iranians developed the Toophan anti-tank guided missile based off the American BGM-71 TOW missile in the 1970s, and reverse-engineered an RQ-170 Sentinel recon drone to create the Shahed-171.

On the part of Defense Express, we are confident that the United States are well aware of the risk posed by russians capturing samples of modern weapons, since it is a common issue of any war. Furthermore, take Stinger for example, it was previously supplied to Afghanistan as well back in 1986 when this missile was a true novelty, despite the risk.

Year after, in 1987, the Soviet Army captured over 100 of these systems and analyzed them in detail. However, the famed reverse-engineering did not lead to a Soviet Stinger analog appearing because this missile uses a dual-channel homing head operating both in IR and UV spectrum.

Precisely speaking, first multi-channel homing head for an AA missile was developed in russia only in the early 2010s, with the introduction of the Verba man-portable missile, adopted by the russian military in 2014. In other words, it took 27 years for the russian military industry to create a weapon with a similar principle.

As for iran, it was successful in creating the Toophan anti-tank missile because before the revolution, it had a repair and maintenance center for BGM-71 TOW, the country overall had quite a potent military industry based on Western technologies.

Considering the RQ-170 Sentinel reverse-engineered into Shahed-171, we should remind you that it's all nothing but claims by iran itself. A drone is not just the glider, it must also have all the high-tech internal systems and a remote control station. To recreate them, one needs to have all the technological resources to reproduce all these components. On the other hand, duplication of the outer looks alone seems more like a "cargo-cult" than actual reverse-engineering.

Another illustrative example: during the NATO operation in Yugoslavia, an F-117 stealth aircraft was shot down; as it was reported at the time, some of the wreckage was brought to the russian federation for study. First of all, it was about recreating the anti-radar coating, but, as it turned out, the russian defense industry has not yet mastered its production. In particular, we can see an example of this on the Kh-101 "stealth" cruise missile, which is covered with ordinary paint.

With Javelin, the situation may turn out even more interesting. The thing is, the russians know well about all the basic design features of this anti-tank missile made back in 1989. However, the issue is where do they find thermal imagers for the homing head and how to produce such a homing head en masse; and no reverse-engineering can help them with it.

In fairness, we should note there are indeed cases in history when reverse engineering resulted in something. This can happen when the difference between scientific and industrial potentials is insignificant. For example, in the 1940s, the USSR copied the Boeing B-29 and mastered the production of the Tu-4. The degree of copying was the highest for all components, but the main problem still was the turbocharger of the engine, which the USSR could not reproduce the 18-cylinder Wright R-3350-23 with the appropriate level of reliability in its own copy called the ASh-73TK.

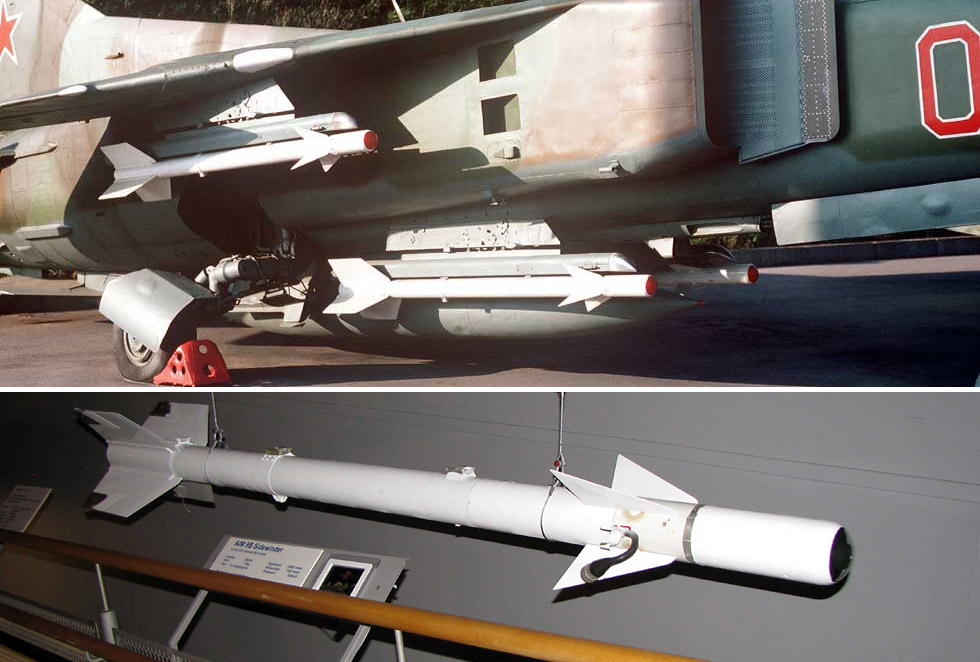

In 1958, the USSR reverse-engineered AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles, which were obtained in various conditions during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, and also thanks to a Swedish colonel who provided detailed drawings. As a result, the K-13 missile entered production in 1960.

It was such an exact copy that when it was analyzed by Western specialists, they were surprised by the fact they could take parts from the K-13 and AIM-9 and assemble a working missile out of them. The only exception was the fuel, which could not be reproduced in the USSR, and therefore the K-13 had a significantly shorter effective range, and so they Soviet pilots tried to launch it only from a close distance up to 2.5 km. Moreover, the homing head of the Soviet missile worked more slowly, and it took 22 seconds to lock the target in comparison to 11 seconds in the original.

However in the late 1960s, USSR was not able to repeat the success by copying the AIM-7 Sparrow missile. The sample arrived from Vietnam in 1967, and the first launches of its copy called R-25 (K-25 is some sources) took place only in 1972. Long terms of the project, problems faced when trying to copy the main nodes and units of this radar-homing missile led to the closure of the project in 1974 and the adoption of the R-23 missile, which was inferior to the AIM-7 Sparrow by all parameters.

On the other hand, reverse engineering becomes much more interesting for a country that, being at a higher technological level, analyzes enemy trophies. It allows such a country to administer its current developments as effectively as possible by understanding the real capabilities of the enemy. And thanks to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, United States laid their hands on a whole bunch of captured russian military equipment, ranging from tanks and other armored vehicles to such rare pieces like the Zoopark-1M counter-battery radar, captured in a fully operational condition.

Read more: Ukraine’s Most Valuable Trophies in Kharkiv Oblast: Why Zoopark-1M Radar And Orlan UAV More Precious Than a Tank Company