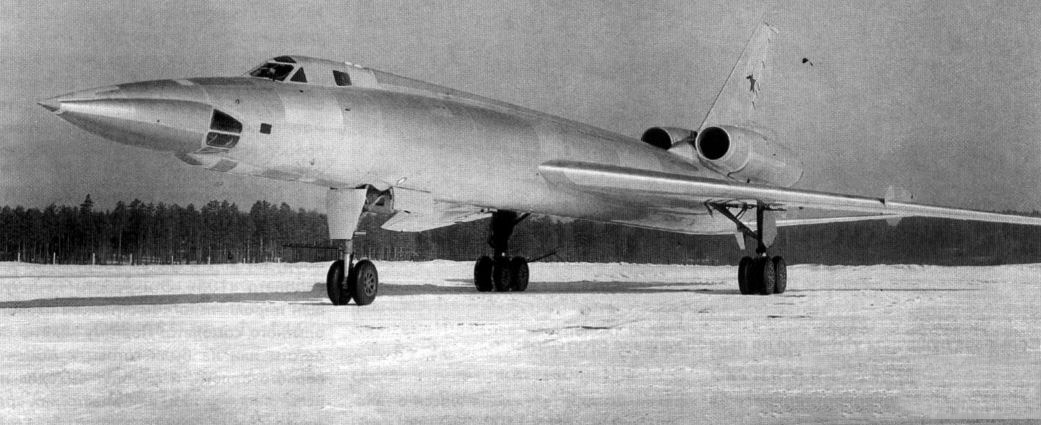

In the history of aviation, some aircraft earned a terrifying reputation due to extreme unreliability, high accident rates, and peacetime fatalities. One of the worst examples is the Soviet Tu-22 bomber, whose prototype first took off almost exactly 67 years ago — on June 21, 1958.

According to most sources, out of the 311 Tu-22s produced, at least 70 were lost in crashes and accidents, which led Soviet pilots to nickname it "The Maneater." Due to the presence of a 380-liter (or 460-liter, according to some sources) tank filled with an alcohol-based de-icing fluid, the aircraft was also called "Shilo" (Awl), referencing the mixture's name.

Read more: UK to Produce Ukrainian UAVs for the War Against russia

One of the bomber's most bizarre features was its downward-firing ejection seats — a decision that doomed dozens of pilots. But why would Tupolev's engineers opt for a design that sent crew members hurtling toward the ground instead of away from it?

The story begins not in 1958, but four years earlier, in July 1954, when the subsonic Tu-16 had just entered service. Tupolev's bureau began work on a supersonic successor, launching two projects simultaneously: "105," using available engines, and a promising "106," intended for future engines. The goal was to create a temporary, interim design that could be upgraded or replaced as soon as better technologies emerged.

This "interim" nature influenced many risky decisions. The new bomber was expected to fly at 1,500 km/h and have a range of 5,800 km at subsonic and 2,300 km at supersonic speed. To meet those goals, the design sacrificed comfort, safety, and even ergonomics.

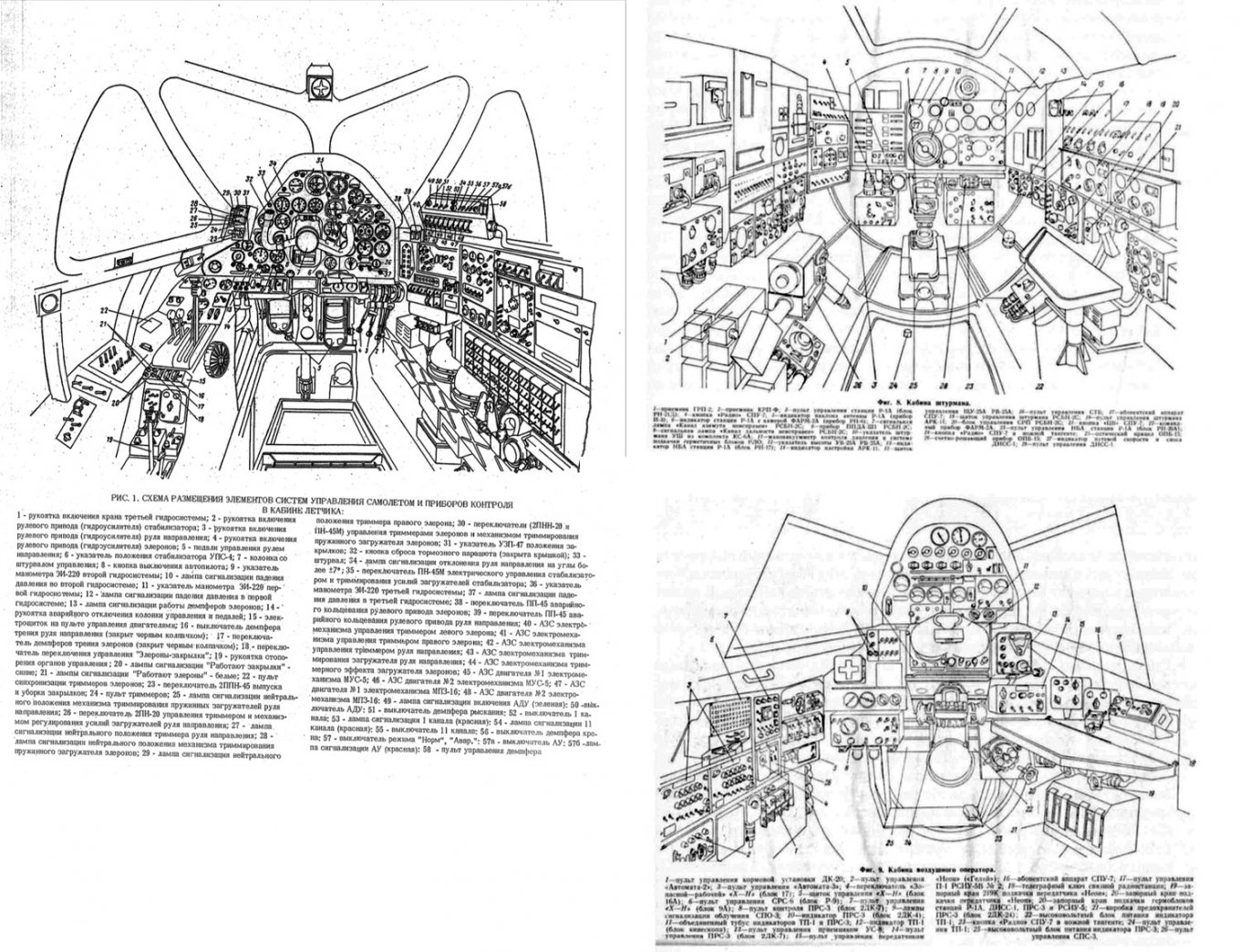

Instead of a spacious two-seat cockpit with multiple crew members, the Tu-22 had a narrow one-man command pilot cockpit, with two more crew members — a navigator and radio operator/gunner — seated separately in the fuselage. All for the sake of reducing the aircraft's frontal area, which, in turn, lowers air resistance and increases its speed and flight range.

The layout was so tight and inefficient that the cockpit became known as a "turned-inside-out hedgehog," due to the chaotic placement of switches and controls, some of which required makeshift wire hooks to operate. It seemed just like the design was made without any understanding of ergonomics.

Each crew member was isolated in their own cramped compartment, surrounded by avionics. Basically, the crew composition and even the seating arrangement resembled that of the Tupolev SB (ANT-40) light bomber from 1940.

The pilot operated from the top seat, sitting slightly to the left — otherwise seeing the windshield divider right in front of him — with blackout curtains installed to shield from nuclear flashes. Right behind him was the radio operator/gunner, while the navigator took refuge in a cabin below. There was zero internal access between positions.

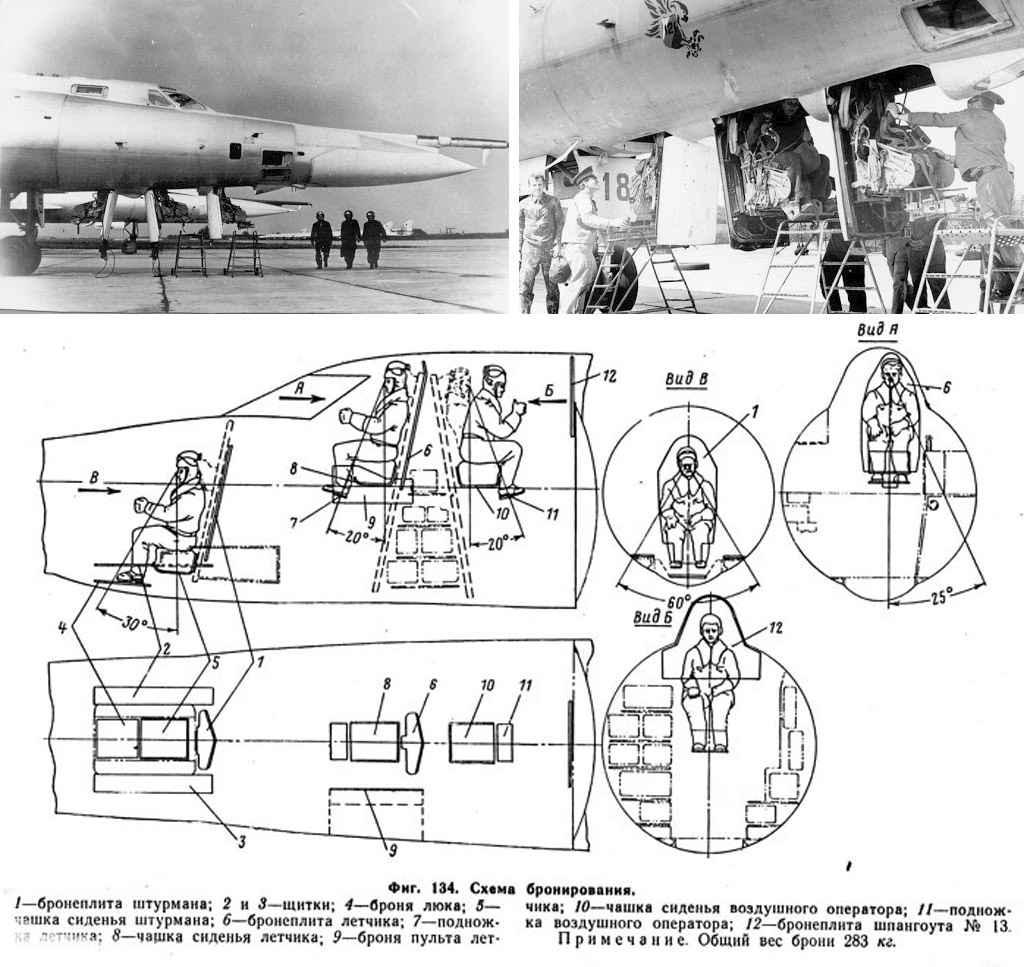

Getting into the plane required external ladders, and eventually, winch-powered ejection seats were added, which were operated manually at first. While this wasn't entirely new (some crew members on the Tu-16 also ejected downward), it became standard on the Tu-22 for all crew, including the pilot.

Why? The decision was likely driven by structural concerns. Adding overhead hatches for upward ejection would weaken the fuselage, especially since the Tu-22 had two massive RD-7M jet engines mounted above the tail — a unique configuration that further complicated upward ejection.

To safely eject upward past the engines and high tail fin at supersonic speeds would've required much more powerful, heavier ejection seats, which didn’t fit in the already cramped fuselage.

Furthermore, before ejection, the pilot, for example, needed his seat to be pulled back into the ejection capsule — impossible with the radio operator being right behind him and vice versa.

The tail-mounted engines themselves were a byproduct of Tupolev's desire for modularity in the "interim" design. He personally decided to abandon recommendations from TsAGI (the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute) and pursued a radically different layout in just 18 months.

The result of these choices was catastrophic. In the Long-Range Aviation branch alone (not counting Naval Aviation), 31 Tu-22s were lost, killing 44 crew members. Only 45 successfully ejected. Due to the compartmentalized layout, many crew members didn’t even know when the pilot had already abandoned the aircraft.

One such incident occurred on May 21, 1973, in the 341st Heavy Bomber Regiment near Zhytomyr, Ukraine. During a tight formation flight of nine bombers, two Tu-22s collided. While one commander managed to land the aircraft despite losing part of the stabilizer, the other silently ejected without warning his crew.

The rear gunner realized what had happened too late — with less than 350 meters left to the ground, he ejected and died instantly. The navigator was heard yelling over the radio, "Commander, don’t descend!" — unaware that he was the last man left onboard.

Read more: russia's Flagship IFV "Terminator" May Have Been Inspired by a 50 Year Old Forgotten German Project