On June 8, 1966, a stunning formation of five aircraft soared above California: the massive white XB-70A Valkyrie led the group, flanked by an F-104 Starfighter, an F-4 Phantom II, an F-5B Freedom Fighter, and a T-38 Talon. It looked like a show of technological pride — but it would end in catastrophe.

The only reason these aircraft of wildly different types were flying in tight formation was a promotional photoshoot ordered by General Electric, showcasing their engines that could break the sound barrier.

Read more: Once Promised to Ukraine, DragonFire Combat Laser Needs Two More Years and €1.2 Bln to Enter Production

NASA's chief test pilot Joseph Walker, flying a brightly painted F-104N to the right of the 242-ton Valkyrie, voiced his concern over the mission in an open broadcast: "I am opposed to this mission. It's too turbulent, and it has no scientific value". He had good reason to worry — Walker had over 5,000 flight hours and 25 missions on the hypersonic X-15, breaking both altitude and speed records.

But Walker's warning was only heard by other military pilots and airbase personnel at Edwards, who were monitoring the flight. Onboard the Learjet 23 business jet, from which photos were being taken, his message went unheard. The civilian aircraft didn't have compatible communications equipment with the military channels.

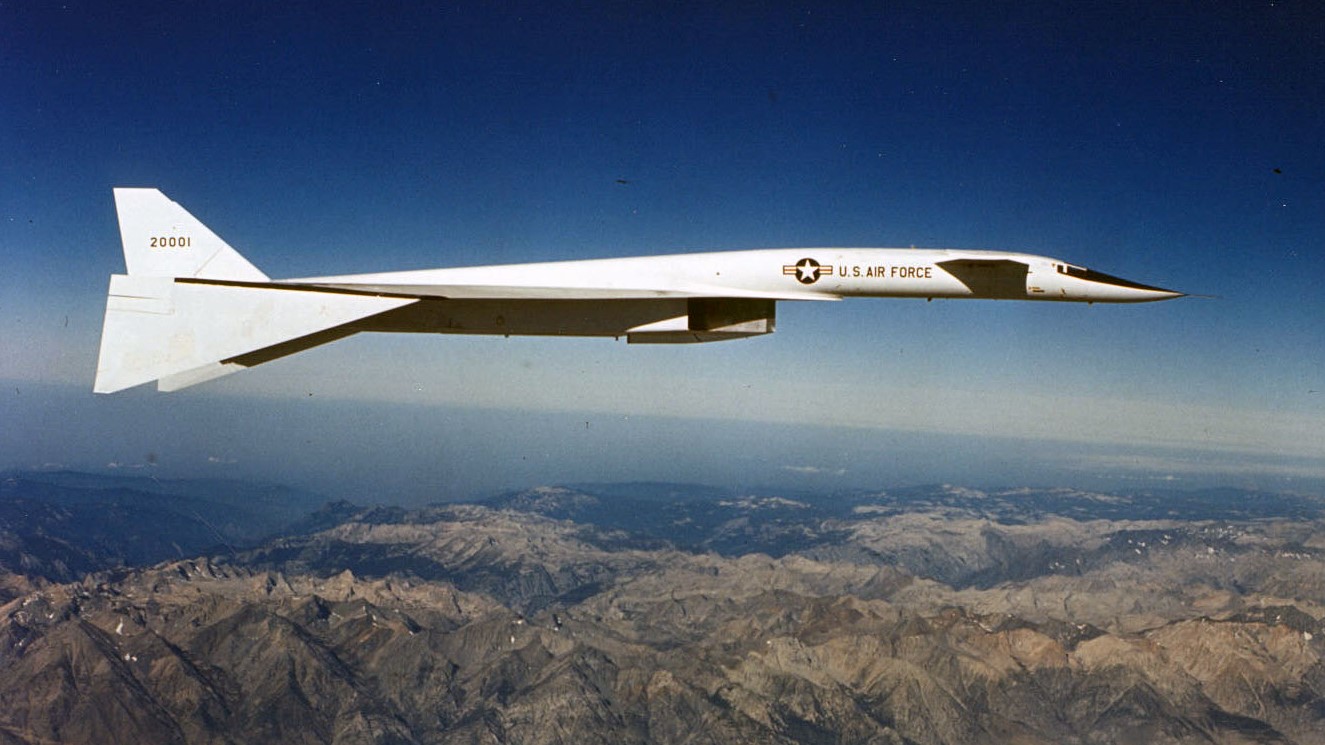

Even the Valkyrie crew didn’t feel comfortable. The XB-70A was never meant to cruise at subsonic speeds. Designed for strategic nuclear strikes at Mach 2 in the stratosphere, it suffered from severe aerodynamic instability at lower speeds. The only way to stabilize the aircraft was to accelerate — something the slower Learjet couldn’t do.

Then the disaster struck. Walker's F-104 accidentally clipped the Valkyrie's right wing with his left wing. His jet flipped over and sheared across the bomber's twin vertical stabilizers like a blade. The fuel leaking from his damaged external tank ignited instantly from the Valkyrie's hot engines. In a matter of seconds, the F-104 turned into a fireball and exploded mid-air. Joseph Walker died instantly.

The Valkyrie struggled to stay aloft for 16 more seconds. Then it rolled right and nose-dived. A portion of the left wing broke off under the stress, and the aircraft entered a flat spin. Chief North American test pilot Alvin White managed to eject and survive. Co-pilot Carl Cross, with 8,500 hours of flight experience to his name but flying the XB-70 for the first time, tragically could not escape.

The XB-70A-2 Valkyrie (serial number 62-0207), the second prototype, crashed in the Mojave Desert, 18 kilometers from Barstow, California. This catastrophe ultimately buried the project, which was on the verge of being realized with the technology available at the time.

The official investigation blamed Walker for failing to maintain a safe distance and not keeping the Valkyrie's wing in view, instead relying on the fuselage as a reference point.

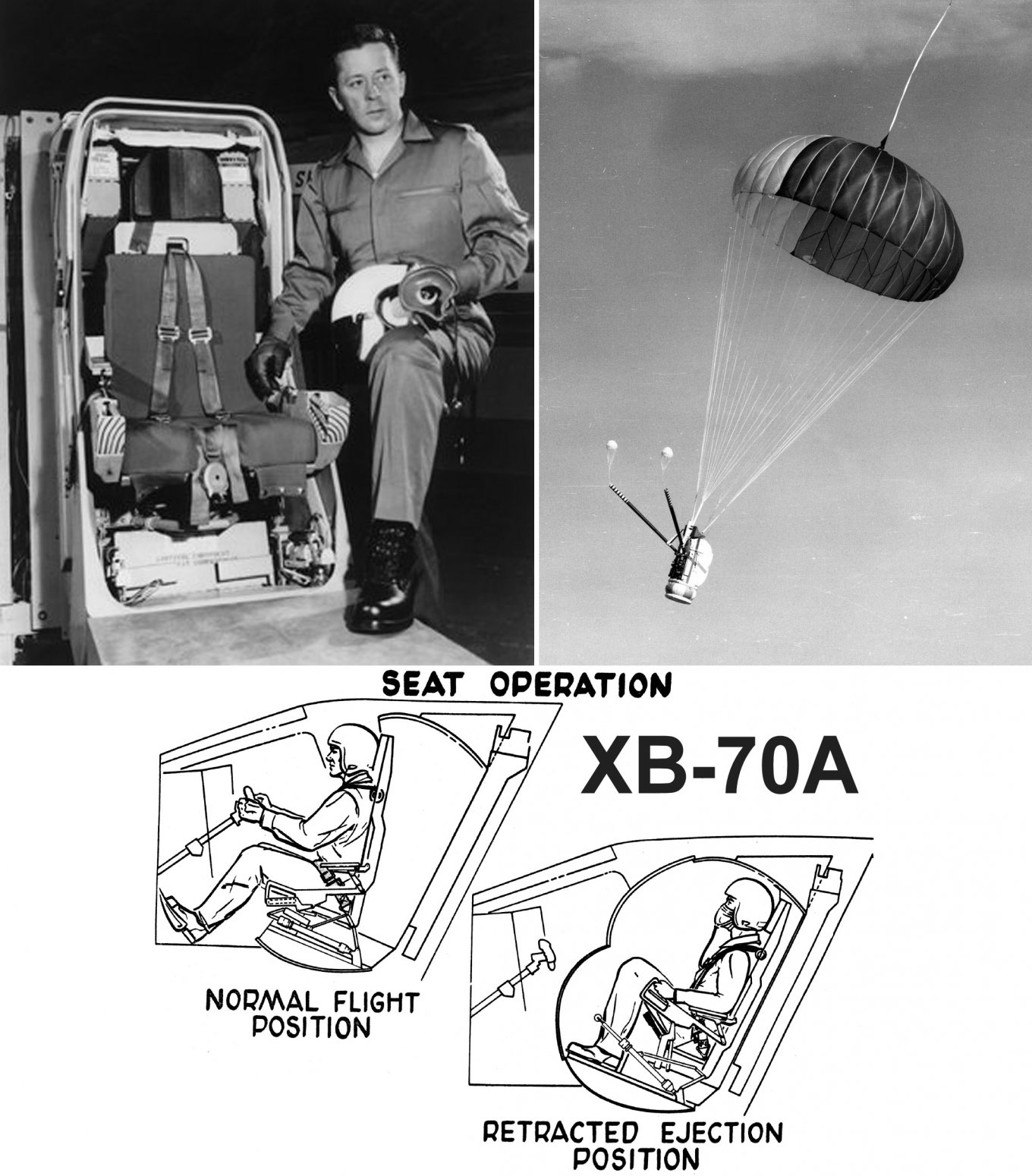

As for why co-pilot Cross couldn't eject, the likely culprit was the aircraft's unusual ejection system, which was borrowed from the Convair B-58 Hustler. In it, the pilot seat was enclosed in a capsule designed to protect the crew at altitudes of up to 24 kilometers. However, the mechanism that pulled the seat back into the capsule required stable flight — and the Valkyrie, spinning like a centrifuge, created G-forces too extreme to retract the seat properly.

The crash caused a massive backlash. The Valkyrie had already faced political resistance. Since development began in 1954, the project had consumed $800 million by 1961 — equivalent to $8.5 billion in today’s dollars. The plant alone for producing specialized zip fuel cost $45 million ($496 million in 2025), only to be scrapped later.

By the 1960s, some already considered the concept of high-altitude penetration bombers already outdated, especially Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Still, strong Congressional support of the Valkyrie project managed to keep it alive, albeit as an experimental project. Initially planned for three aircraft, the production was cut to two.

The first prototype rolled out on May 11, 1964, and flew for the first time on September 21. The second prototype, completed on October 15, didn't fly for a year until January 3, 1966. This pause was due to the fact that the second prototype immediately eliminated all the shortcomings that were noticed. For example, the airplane's skin was modified because the initial prototype was blown away at speeds over Mach 2.5, and an automatic air intake control system was installed.

It was the wedge-shaped air intake, which would later be used on all similar aircraft (for example, the American B-1 and the Soviet T-4 and Tu-160), that was the central element that allowed the XB-70A Valkyrie to have such characteristics. Because at supersonic speeds, it formed an area of increased pressure under the wing, reinforced when the wing was lowered down.

It was the second prototype, the XB-70A-2 Valkyrie (serial/number 62-0207), that achieved the speed of Mach 3 (Mach 3.05) required by the U.S. Department of Defense. This was done on January 3, 1966, at an altitude of 22 km. On May 19, 1966, the second requirement was met — the speed of more than Mach 3 was maintained for more than 30 minutes (Mach 3.06 for 32 minutes). In total, it flew 3,900 km in 91 minutes. This was enough time to fly to Moscow and back in 1.5 hours, taking off from an air base in Denmark, Norway, or Turkey.

But on June 8, 1966, the only prototype that could achieve such flight parameters crashed. And with it, the only argument in favor of reinstating the aircraft as a military development rather than keeping it purely experimental. The first prototype continued NASA's limited testing program for another 2.5 years until December 17, 1968, and afterward, the unique vehicle was transferred to the U.S. National Air Force Museum.

Read more: moscow Hides Its Tu-160 Strategic Bombers At Air Base 6,750 km from Ukraine