The F-15 remains one of the most powerful fighter jets in the world and has no plans for retirement, even as it celebrates its 53rd anniversary today, July 27. The reason is simple: the F-15 is a true monster in terms of combat load. It can unleash nearly a dozen and a half AIM-120 AMRAAMs against airborne targets or transform into a "bomb truck."

It holds the record for the most enemy aircraft shot down in modern history. The F-15 is credited with 103-104 kills (depending on the source) and even one satellite destroyed using the ASM-135 ASAT missile. Remarkably, no F-15 has ever been shot down in an air-to-air battle. Throughout its history, only three F-15Es have been lost to ground fire during both Iraq wars. That's out of approximately 1,200 aircraft produced. Apart from the United States, only Israel, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar could afford to operate this fighter.

Read more: Izdelie 180 / K-77M / R-77M: What We Know About russia’s New Long-Range Missile

It all began in 1965 when the U.S. Air Force faced uncertainty in its future development. At the time, its inventory was a "zoo" of various fighters, fighter-bombers, and interceptors designed and adopted in the 1950s: the F-100 Super Sabre, F-101 Voodoo, F-102 Delta Dagger, F-104 Starfighter, F-105 Thunderchief, and F-106 Delta Dart. The F-4 Phantom II was being deployed, and the F-5 Freedom Fighter had entered export production.

Meanwhile, the idea of creating a single universal heavy super-fighter for both the Navy and the Air Force under the Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX) program, which led to the F-111, ultimately produced only a bomber for the Air Force. The F-111's cost prevented it from becoming truly mass-produced, and it was suitable only for a large-scale war against the USSR. However, the U.S. was already fighting in Vietnam, with Korea behind and a firm belief that another conflict in the Third World was inevitable. Thus, there was a need for mass-produced aircraft.

Ideas emerged to compensate with a light, multifunctional aircraft — either an upgraded A-7 capable of full-fledged air combat or an enhanced F-5 with improved ground strike capability. Both options met with skepticism, though support leaned toward the A-7.

Within the Air Force itself, a group of generals pushed for the development of an air superiority fighter. Thus, the concept of a "medium fighter" under the abstract name F-X emerged. Due to budget constraints, the program was disguised as a Close Support Fighter capable of ground strikes. In April 1965, the project received funding and approval from the powerful Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who sought to eliminate the aircraft "zoo."

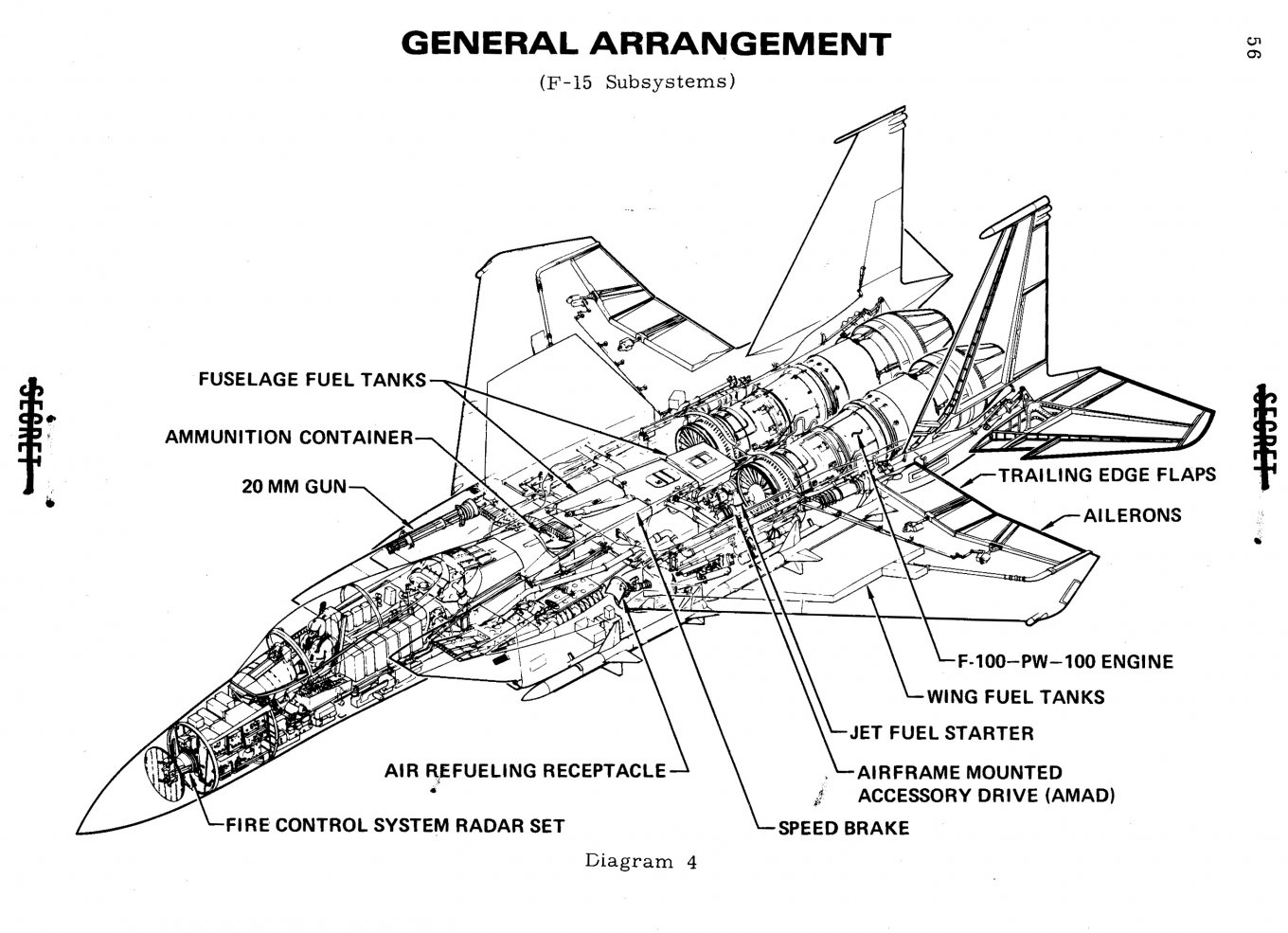

Early sketches of the F-X envisioned advanced avionics and variable-sweep wings, like those on the F-111. The aircraft would reach Mach 2.7, carry large amounts of ordnance — 1,000 rounds for its 20mm M61 gun, four air-to-air missiles, or up to eight Mk 82 bombs (500 lbs / 230 kg), or 4,000 lbs (~2 tons) of other ordnance. This translated into a takeoff weight of 60,000 lbs (27 tons), a thrust-to-weight ratio of 0.75, and a wing loading of 110 lbf/ft² (537 kg/m²).

Then came Major John Richard Boyd, a legendary figure who, using unauthorized access to a supercomputer, developed the energy–maneuverability theory. Thanks to this theory, which gained traction in Pentagon circles, the F-X in 1967 slimmed down to 40,000 lbs (18 tons), with a thrust-to-weight ratio of 0.97 and a top speed of 2.3–2.5 Mach. Boyd also advocated for a wing loading of 60–65 lbf/ft² (293–317 kg/m²).

By the summer of 1967, the F-X was repositioned as a replacement for the F-4. A budget plan was announced: $7.183 billion total, including $615 million for research and $2.468 billion for the first five years of operations.

The plan was to order 1,000 aircraft at $2.84 million each, with deliveries starting in December 1973. In 2025 dollars, that equates to $69.34 billion for the whole program and $27.4 million per aircraft.

In 1968, the F-X program was given top priority, influenced by lessons from Vietnam, where air combat turned into dogfights. However, the order was cut first to 635 and then to 520 aircraft. Unit cost doubled to $5.3 million ($51 million today), and the total program cost rose to $8.128 billion ($78.52 billion today).

Additional pressure came from intelligence about the Soviet E-155 program, which would become the MiG-25. Though it was a late response to America's high-speed, high-altitude concepts, already abandoned, it still prompted concern.

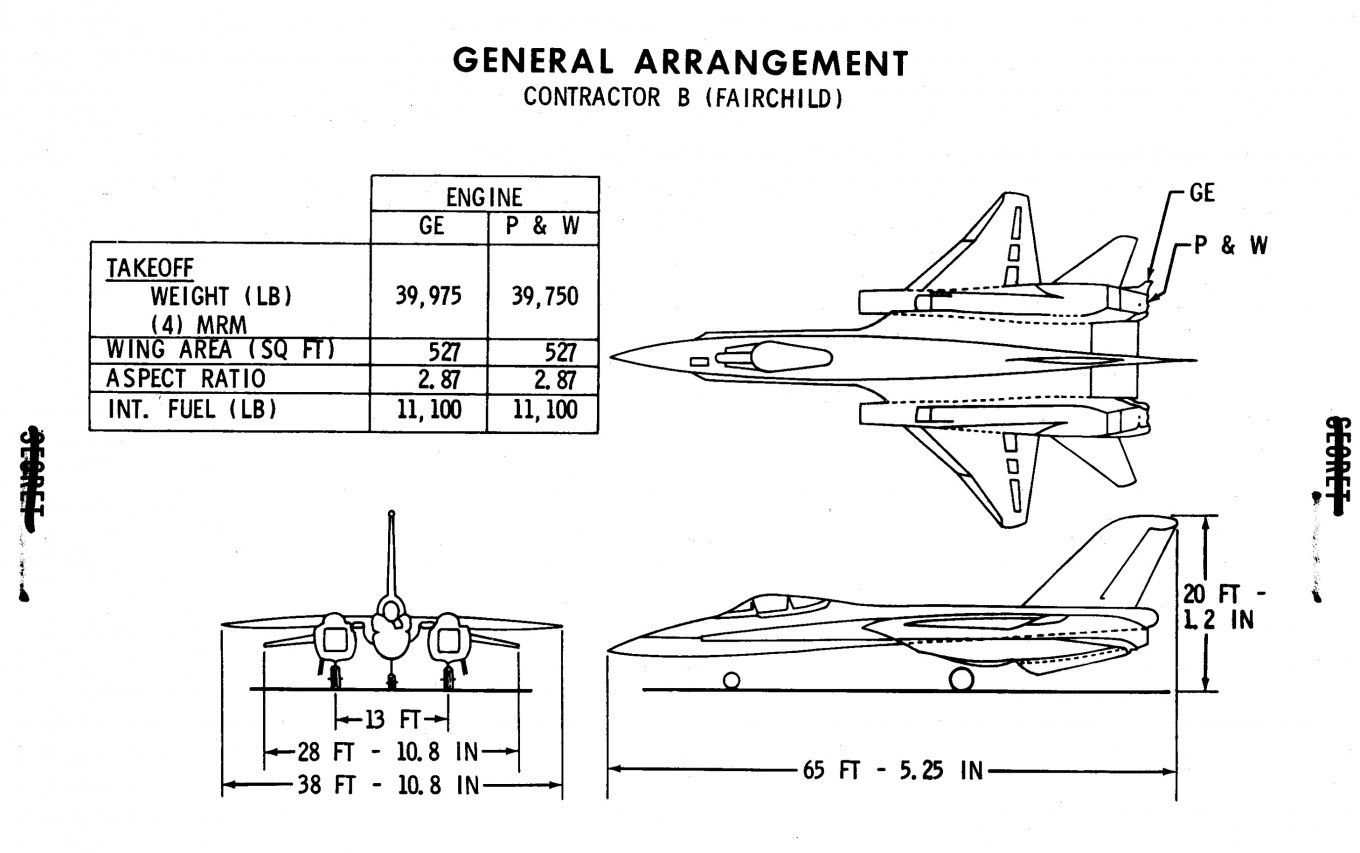

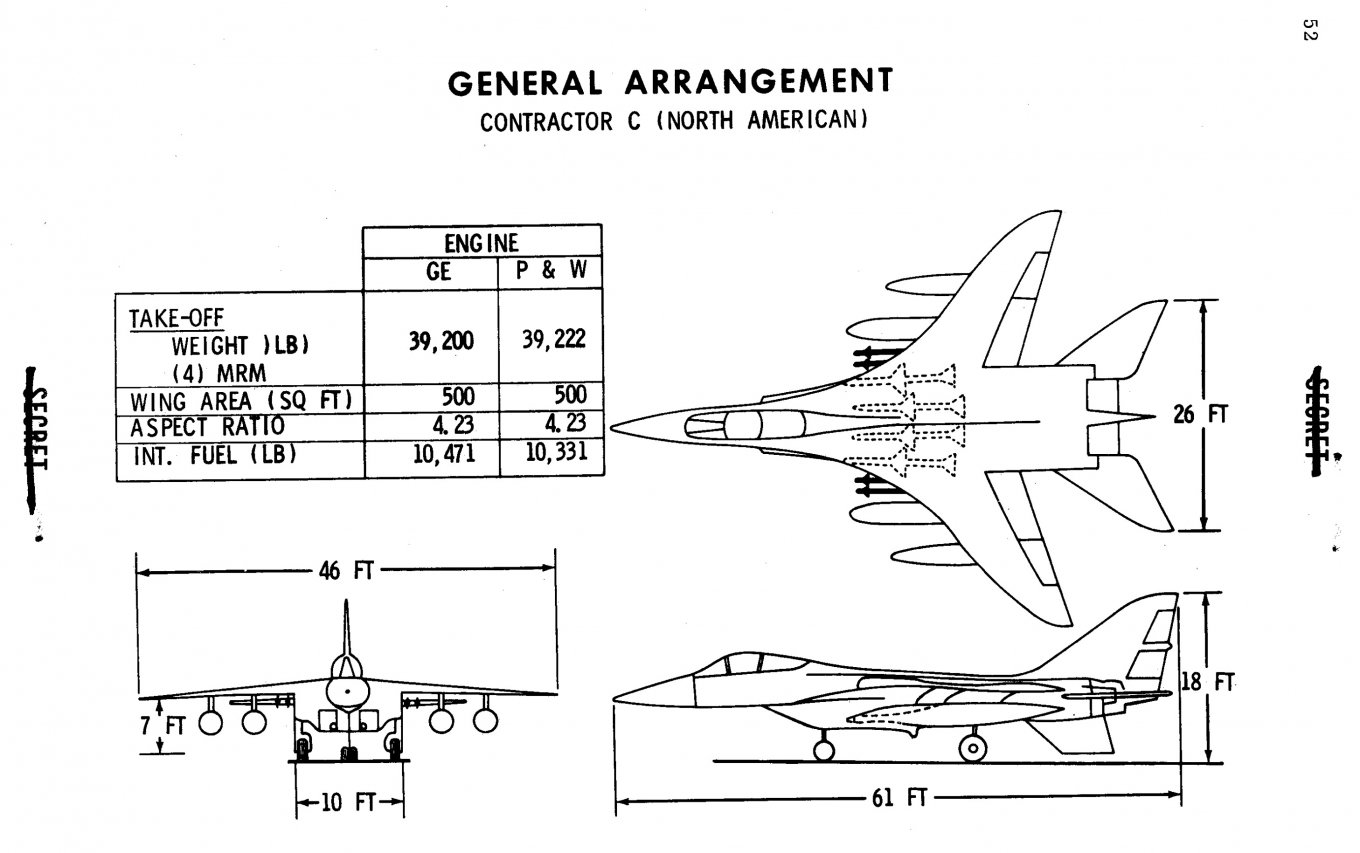

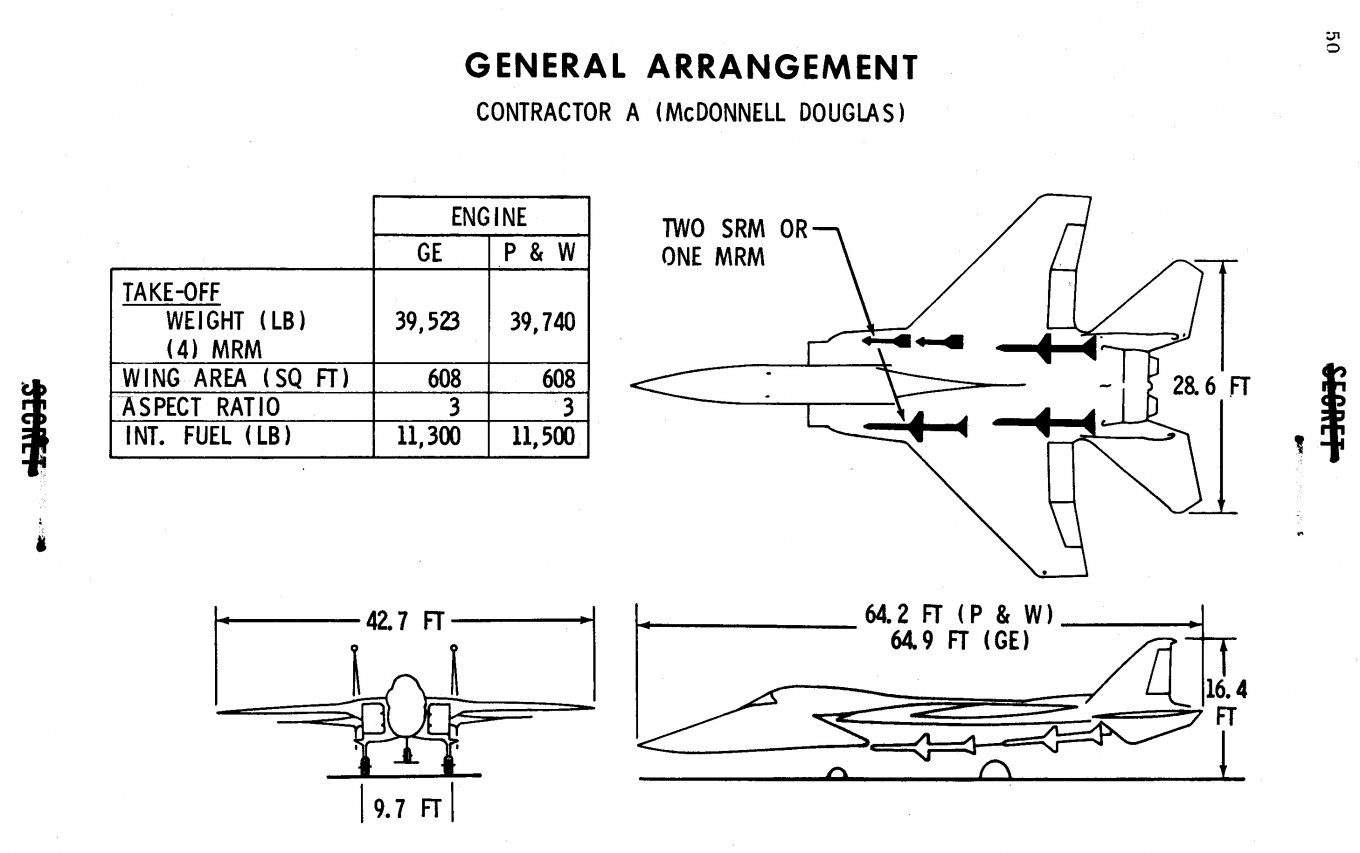

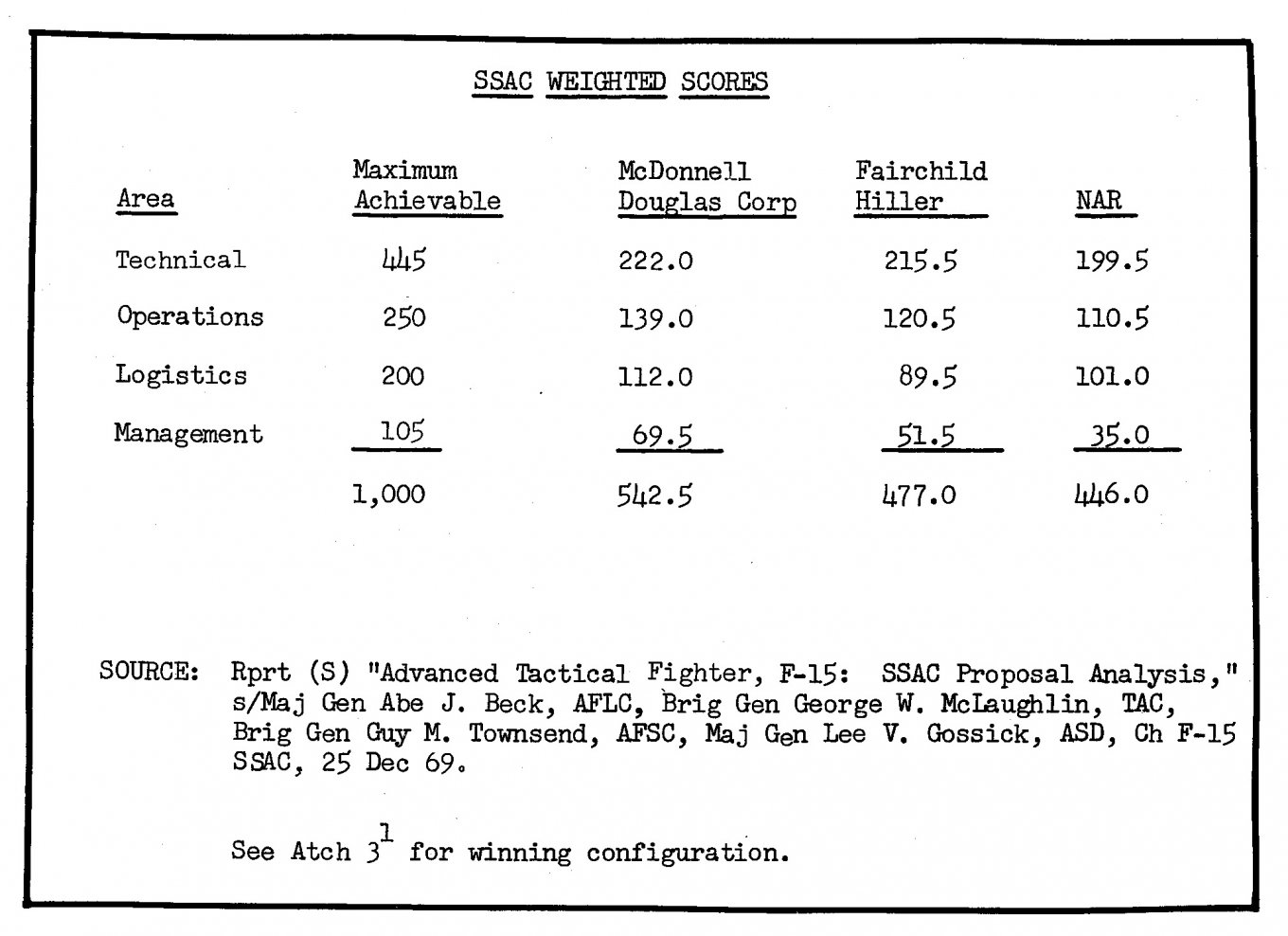

In September 1968, final proposals were requested. Fairchild-Hiller, North American, McDonnell Douglas, and General Dynamics submitted bids. All except General Dynamics received $15.4 million to develop prototypes. Designs were presented in July 1969.

Fairchild-Hiller proposed a design with widely spaced engine nacelles, improving survivability by making it harder to disable both engines and solving aerodynamic issues from gun gas ingestion. However, this compromised single-engine handling.

North American proposed the NA-335, a sleek design using a lifting-body fuselage with integrated wing structure. Engine placement and intakes were inspired by their XB-70 Valkyrie experience.

McDonnell Douglas presented the future F-15 with the largest wing area, the largest fuel tanks, and the lowest cost.

Their proposal scored highest in all four evaluation categories. The F-15 contract helped offset the end of F-4 production, which still continued until 1981.

On December 23, 1969, McDonnell Douglas won the contract. Designing and producing the first 20 aircraft would cost $1.1 billion.

Unlike Soviet design traditions focusing on a single brilliant chief designer, McDonnell Douglas's general director said the company spent 2.5 million man-hours to win the contract. A team of initially 200, later growing to 1,000, worked for two years, studying over 100 alternate projects and thousands of variations.

Competition for the engine supplier followed, with Pratt & Whitney winning with the F100-PW100. Hughes Aircraft won the contract for a radar targeting system operable by a single pilot, capable of tracking ground targets.

Calculations showed the F-15 had clear superiority over the MiG-25 in specific power and wing loading: 1.1 and 65 lbf/ft² (317 kg/m²) for the American jet, versus 0.78 and 98 lbf/ft² (478 kg/m²) for the Soviet one. Later estimates revealed the MiG-25's real performance was lower: thrust-to-weight of 0.66–0.68 and wing loading of 585 kg/m².

On June 26, 1972, the first prototype YF‑15A was unveiled at McDonnell Douglas's St. Louis factory, receiving the official name Eagle. Nine more prototypes were already under construction.

After the ceremony, the aircraft was repainted with orange trim and flown on a C-5 to Edwards Air Force Base, where McDonnell Douglas test pilot Irving Burrows flew it for the first time — exactly 53 years ago on July 27, 1972.

Within six months, the Pentagon ordered serial production. The F-15A became a pure air superiority fighter with secondary strike capability, aligning with Boyd’s theory and Air Force requirements — and even exceeding them.

Empty weight was 41,500 lbs (18.8 tons), maximum takeoff weight 56,000 lbs (25.4 tons), top speed Mach 2.5, thrust-to-weight ratio (empty) 1.07, wing loading 73.1 lbf/ft² (357 kg/m²). Armament: four AIM-7F Sparrow and four AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles.

A total of 384 single-seat F-15As and 61 two-seat F-15Bs were built, entering service in 1976. Meanwhile, modernization work on the F-15C/D under the Eagle Package (PEP 2000) program added 900 kg of fuel, conformal tanks, increased max takeoff weight to 68,000 lbs (30.6 tons), and new F100-220 engines.

The F-15C/D was adopted in 1979, with further MSIP upgrades in 1983 including an improved central computer, updated weapons, and powerful electronic warfare systems.

In parallel, the F-15E Strike Eagle was developed starting in 1981, with a 10.5-ton bomb load — half a ton more than the B-29 Superfortress. It won the Enhanced Tactical Fighter competition to replace the F-111, aiming to perform deep strike missions combining air and ground attacks without external support.

In 2020, the Pentagon ordered the F-15EX, ensuring the aircraft remains in U.S. service for decades to come. Israel has also selected this variant, despite already operating F-35s. The F-15EX continues to offer capabilities still unmatched by other jets.

Historical references in this Defense Express article are based on the book The F-15 Eagle: Origins and Development, 1964–1972 by Jacob Neufeld, published in 1974 for internal use by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of Air Force History and declassified in 2008.

Read more: russian SU-27UB Fighter Jet Destroyed Overnight at Armavir Air Base