November 21st, russia launched a yet unidentified intercontinental missile at Ukraine. While the speculations continue if it was the RS-26 Rubezh intermediate-range ballistic missile which is usually a carrier of nuclear charges, we can shift the angle and take a look at the symmetrical response capabilities of NATO and the USA particularly.

For a reminder, deployment of intermediate-range and a number of shorter-range missiles was prohibited by the INF Treaty from 1987 to 2019. But the agreement is no longer valid after the russian federation violated its terms by fielding Iskander-K and the RS-26 Rubezh systems. And if you dig deeper, even the Soviet allegedly compliant Topol missile did not actually meet the terms of the treaty either.

Read more: How ICMBs and IRBMs Work: Incident Reconstruction of russia’s RS-26 Rubezh Missile Strike on Dnipro

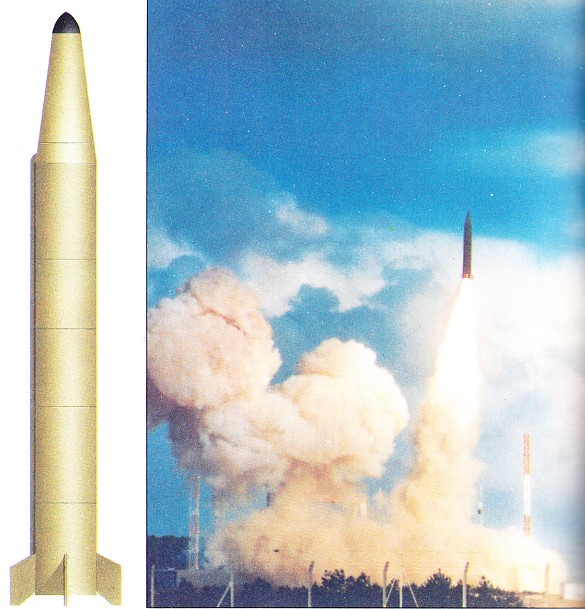

Be that as it may, the year 1987 became the point where systematic disposal of intermediate-range missiles began in the USA and the USSR. First of all, the trend applied to Soviet RSD-10 Pioneer and the American MGM-31 Pershing and Pershing II. All these missiles were destroyed or deactivated by 1991, and became rare specimens in museums.

Worth noting, not only the USA had such ballistic missiles in NATO. American Pershing I was also in service with the German Bundeswehr albeit they were decommissioned in 1991, too, under pressure from Washington.

In total, about 750 Pershing I were produced throughout history. The missile had a maximum range of 740 km (460 mi) and carried a single nuclear warhead with a yield of 60 to 400 kilotons. Then, Pershing II appeared, with more than 270 units made. The second generation had a range of 2,400 km and an improved guidance system allowing to decrease the explosive yield down to 5–80 kilotons while retaining the same effectiveness.

In the 1980s, France was keeping the S-3 silo-based intermediate-range ballistic missile on combat duty. Only 40 such missiles were produced in total, each carrying a 1.2-megaton nuclear warhead to deliver at distances up to 3,500 km (2,175 mi).

But Paris completed their decommissioning by 1999 without replacement and dismantled all the ground launch infrastructure.

Though on the other hand, the collapse of the INF Treaty worked both ways, and the U.S. shortly began creating long-range weapons that were prohibited while under the agreement. The immediate result of this effort is Lockheed Martin's Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW), also known as Dark Eagle.

The LRHW is an intermediate-range land-based ballistic missile with a hypersonic glider and an operational range of about 3,000 km (1,860 mi). The cost of production is known to be $41 million apiece.

But the problem is that the deployment of the first LRHW battery in the U.S. Army has been delayed and is now scheduled for 2025. The second battery, bought for $756 million, should be deployed by February 2028.

Overall, the United States is planning to deploy five Multi-Domain Task Forces, each including one LRHW battery. But all that is ready as of today is one test division at Cape Canaveral governed by Indo-Pacific command structures.

Meanwhile in Europe, they didn't even start talking of own intermediate-range ballistic missile development. The only closest program, the European Long-Range Strike Approach (ELSA) project, is still limited only creating the Land Cruise Missile — a deep modernization of Storm Shadow/SCALP short-range cruise missiles with adaptation for land-based launchers.

Against this background, we can only add that russia apparently created its RS-26 Rubezh based on two stages of the Topol-M's engine, and therefore has cranked-up facilities that can produce this IRBM in large quantities much faster than the United States can make LRHWs.

Read more: What's the Kub-M Nuclear Blast Shelter: a Case Study of Another russian Corruption Scheme