Often when we hear about the EU project called Military Schengen, the media coverage of this topic makes an impression that it's only about bureaucracy, border guard services, customs, etc. As if in a hypothetical situation, where a russian attack has to be repelled, let's say, in Estonia, the French army would need to get through a sequence of standbys on the border with Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia, until all the troops get their stamps in passports, and all their equipment passes customs check-ups.

Meanwhile in reality, although this project does deal with bureaucracy, it is not so much of a main focus. In fact, the draft of this so-called Military Schengen is no novelty, it appeared long before 2022 when russia launched a full-blown war of aggression against Ukraine, and Europe realized how important this program could prove.

Read more: Long-Awaited New US-made Long-Range Bomb to Arrive in Ukraine

The plan was initially proposed back in 2017 under a bit less remarkable name Military Mobility (MM). It started entering force in 2018, after the European Commission came up with a definite roadmap.

As the name suggests, it indeed outlines the principles of transporting military servicemen, arms, and equipment but those aspects take only a small part of the project. Furthermore, the solutions to the bureaucratic problems, offered in this plan, one way or another apply only to peacetime.

In particular, there is the necessity to warn other countries about relocations of forces or to receive permits for transportation of dangerous (like ammunition) and bulky supplies. But if a real war broke out, there would hardly be anyone willing to deal with all of that, even despite the stereotypically high levels of the European bureaucracy. As for the peaceful times, all these issues are supposed to be managed by a unitary digital system scheduled to start operating in 2025.

But as we mentioned earlier, this is only a small part of a much broader range of tasks. The Military Schengen is first and foremost about logistics, which is objectively the most important factor in a war because the capability to relocate and deploy forces and provide them with necessary supplies is the foundation of overall defense capability.

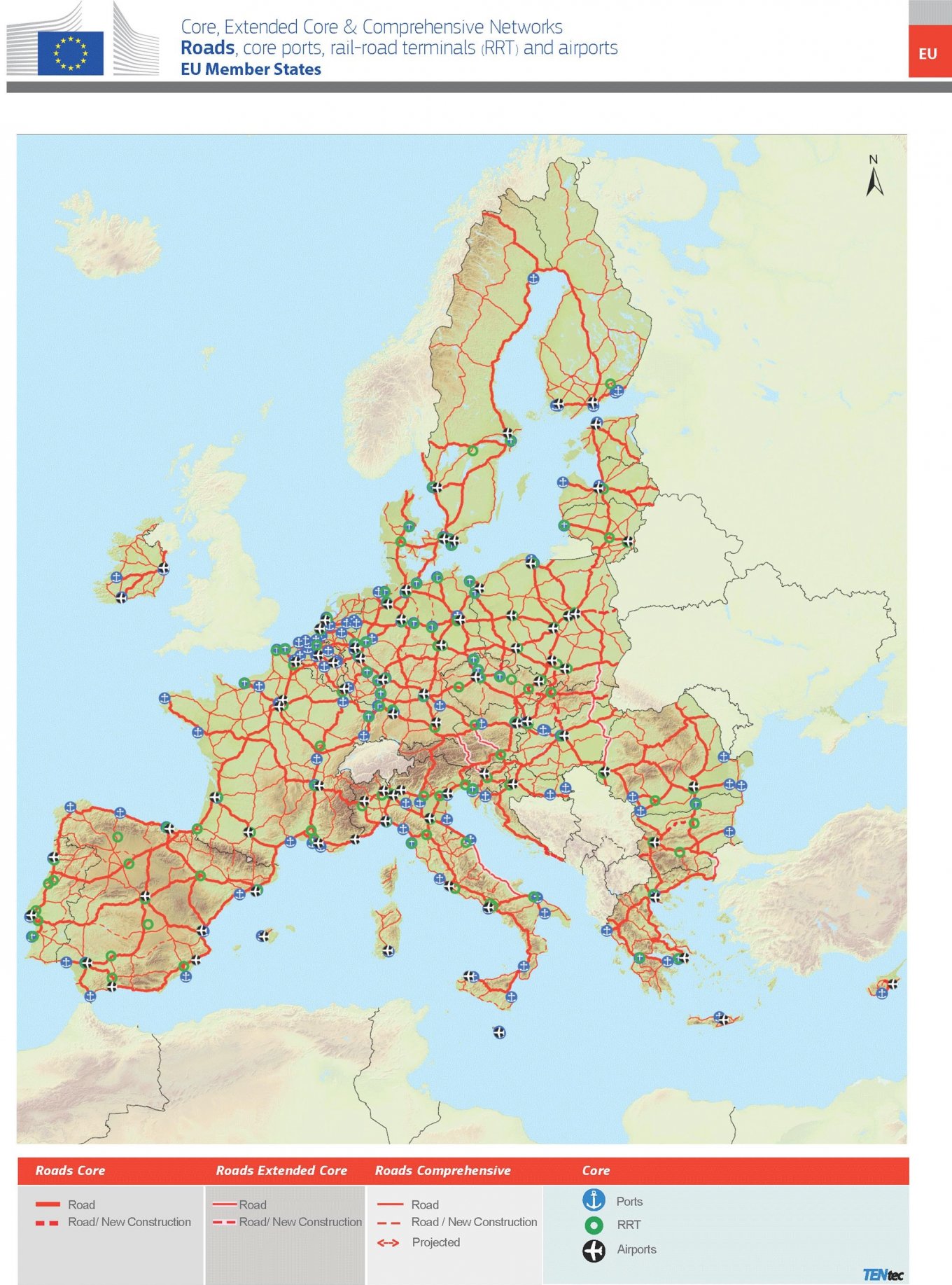

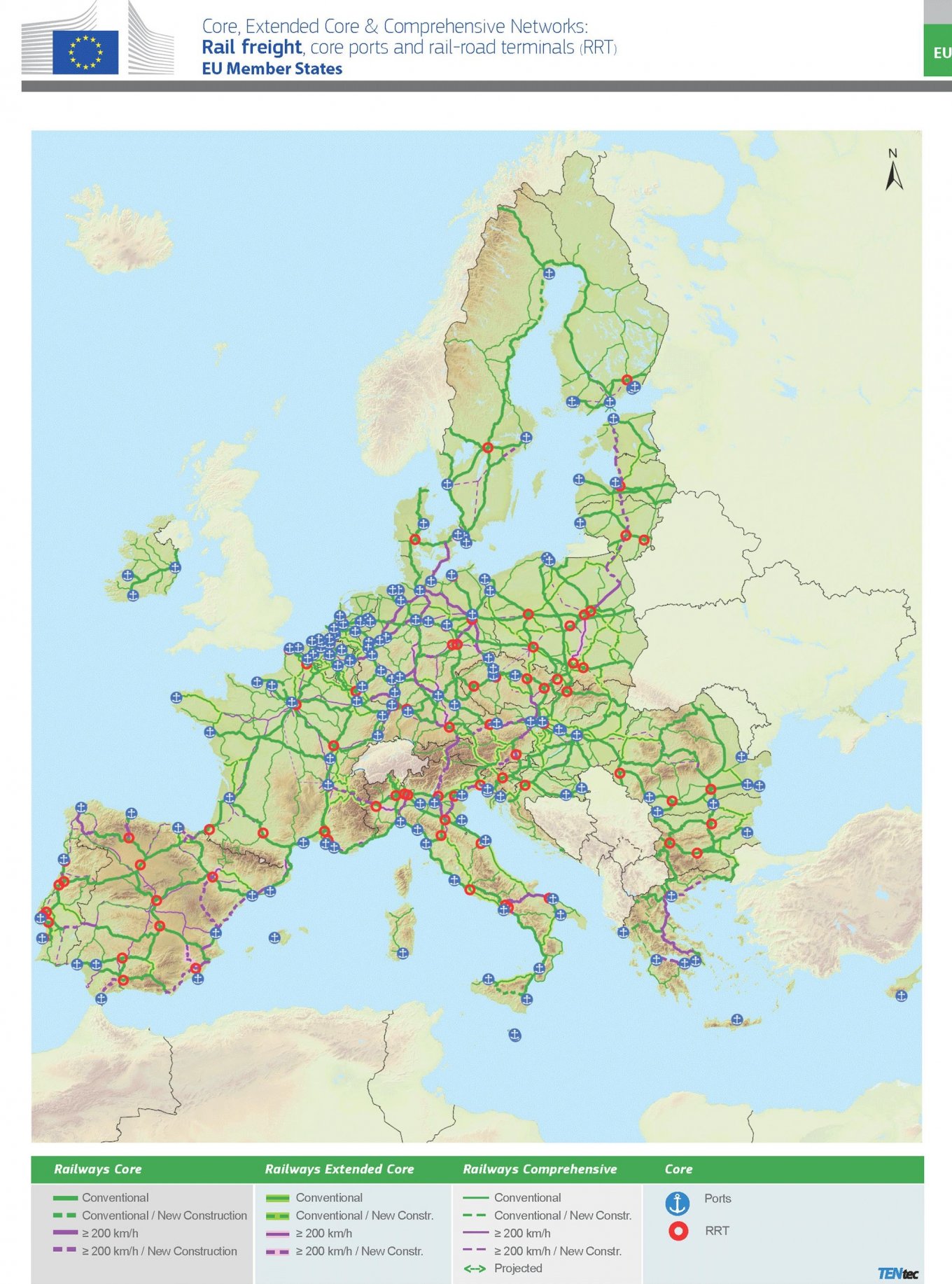

In other words, the Military Schengen in Europe is about roads, bridges, logistic hubs, and warehouses. Addressing these issues takes most of the resources in the plan offered by the European Commission, and there is actually quite a lot to address.

For example, Romania has to repair its roads in order to make them passable for M1 Abrams. After all, the roads must endure the weight of a 66.8-ton M1A2 SEPv3 tank, plus the weight of the truck carrying it. The same goes for railways which have seen no maintenance or replacement for dozens of years.

Similar or the same problems pertain to many countries in Western Europe as well. A typical armored vehicle has become heavier over the past 20 years, a period when countries were spending less on defense in general and giving up on main battle tanks because of these exact problems related to transportation.

It's not as if there were no proper bridges at all, just too few of them. The fewer transport routes one has, the less effective the logistic efficiency, the slower the tempo of deployments, and the more vulnerable the transport infrastructure.

It is not limited to only roads and bridges, though. As mentioned, the EU countries also need hubs to ensure cargo handling, i.e. loading and unloading the goods on and from ships, aircraft, railway, or trucks. That explains why air transport infrastructure is also included in the to-do list of this program.

Finally, one more key aspect of the Military Schengen is the intent to create a united logistics network, where supply and maintenance of military equipment of different European countries adhere to a common standard. That said, the Military Schengen is more complex than it might seem at first glance.

Read more: North Korea–russia Ammunition Supply Routes and Main Depots Analyzed