The fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime, logically, should also lead to the termination of the russian military presence in Syria. But how exactly this will happen is a separate and rather interesting question because, on the one hand, events are developing at a galloping speed: Israel has already launched an airstrike on the naval base in Tartus which russian ships use, and in the meantime, the Kremlin is hastily preparing a Syrian Express made of evacuation planes and ships.

At the moment, there are only two options for how the russian federation will leave Syria: either it will be a fast empty-handed escape or a long process agreed upon with the new Syrian authorities. This is according to an assessment that Dara Massicot, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment, has shared on social media.

Read more: Israeli Forces Strike Base in Tartus, Where russian Ships May Still Be Present

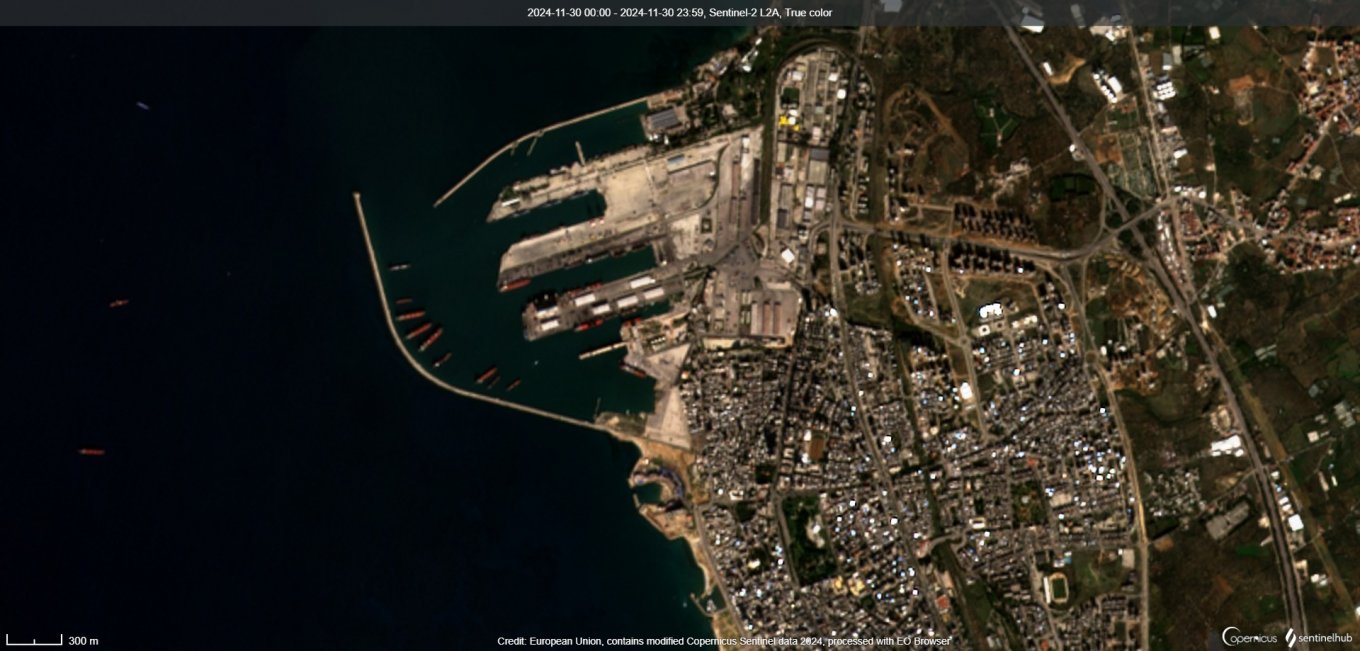

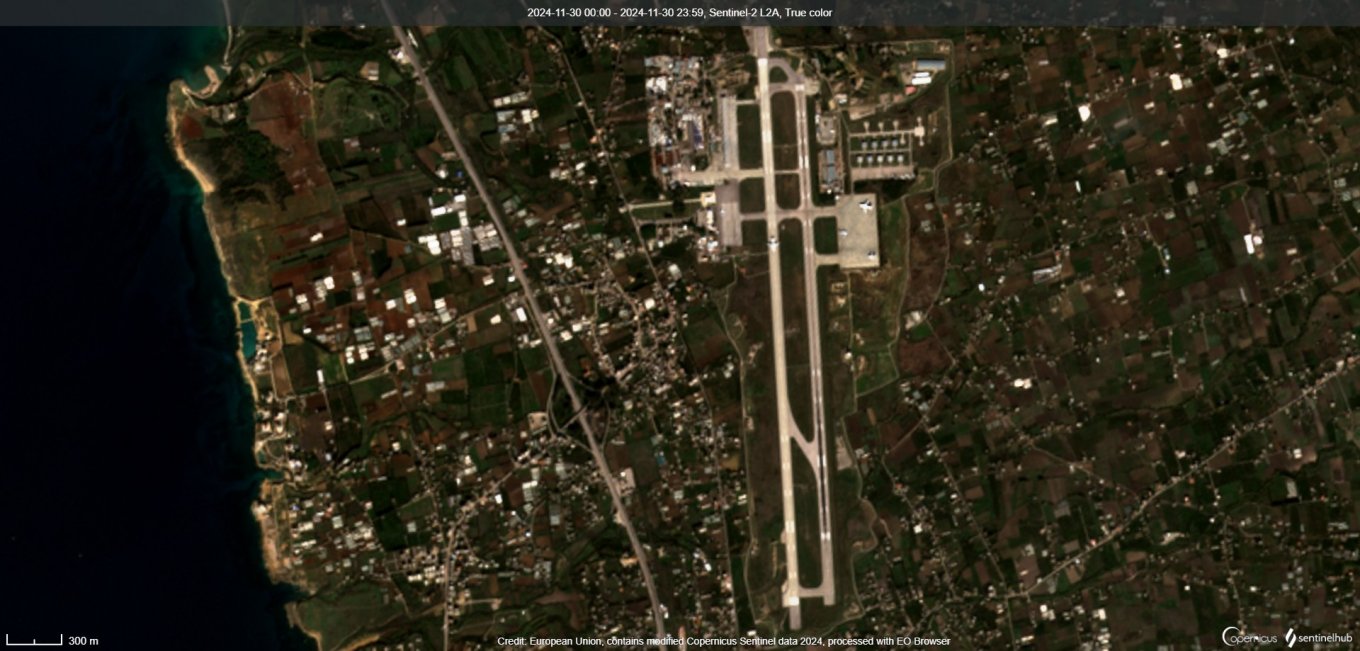

Specifically, the expert stressed that russia had imported its military equipment to Syria for years, starting September 30, 2015. In total, two bases were deployed in the country: the Khmeimim Air Base and the 720th logistics hub of the russian Navy in the port of Tartus.

The only sea route for evacuation to russia lies across the Baltic Sea because Turkey keeps the Bosphorus strait closed to warships. Also, an alternative under consideration is through the ports of Libya, Sudan, or Algeria.

On a note from Defense Express, we would like to add that any attempt to carry weapons by civilian ships to the ports in the Black Sea would be an invitation to a drone strike from Ukraine using its unmanned kamikaze boats.

At the same time, organizing an air bridge to russia is unlikely to work at all. Air evacuation will require hundreds of flights by Il-76 and An-124 heavy strategic airlifts. To compare, when the russians were just starting to deploy in Syria, they made 300 flights in two weeks — this was before they expanded their base even further.

Therefore, the intensity of flights recorded in recent days is not a full-fledged evacuation effort. Moreover, an air bridge requires permission from the new Syrian government to pass through its airspace. Until an agreement is reached, the use of the airbase is technically impossible.

There is also a nuance regarding the use of Turkish airspace. The route through Turkiye to the airbases in the Krasnodar Krai spans for 1,000 km. A roundabout way is 1,500 km of travel over Iraq, Iran, Armenia, and Georgia. Every extra hundred kilometers costs not only time but requires taking less cargo, thus necessitating more flights per aircraft.

Based on this, Dara Massicot concludes that Moscow wants to retain possession of the bases and is ready to offer the new Syrian authorities a wide range of payment options: money, weapons, or mercenaries. Whether the Syrians will agree to this is, of course, a question for another time. On the other hand, if they don't, the russians will have only one option left: to abandon everything they brought to Syria and flee with nothing.

Read more: How Ukraine’s Naval Drones Shut Down russia’s Syrian Express in March 2024 and What It Means