While many in Ukraine consider this idea impossible, the F-16 has, in fact, demonstrated the ability to shoot down a ballistic missile. This article explores how that was achieved and why it never entered operational service.

It all began with the U.S. desire to intercept ballistic missiles using aircraft, in a manner similar to the more recent AIM-174 integration with the F/A-18. However, unlike today’s airborne version of the SM-6, the original concept was based on existing air-to-air missiles.

Read more: Who’s Behind the Threat to UK Bases Training Ukrainian Pilots on F-16s and Mirage 2000s?

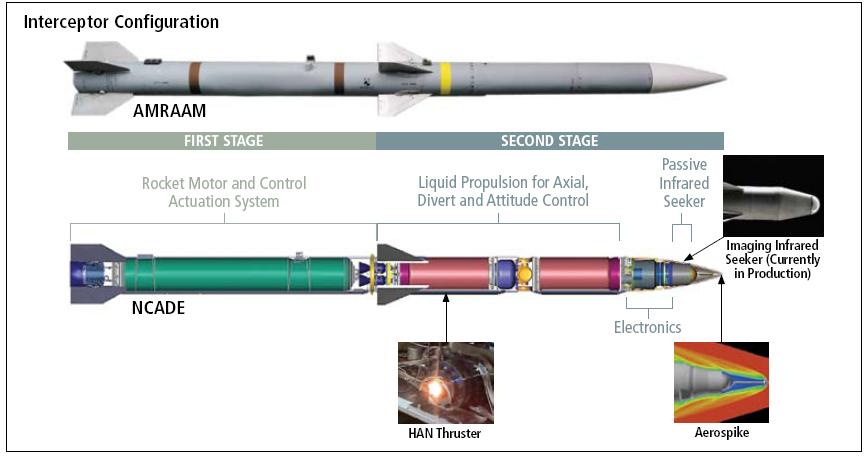

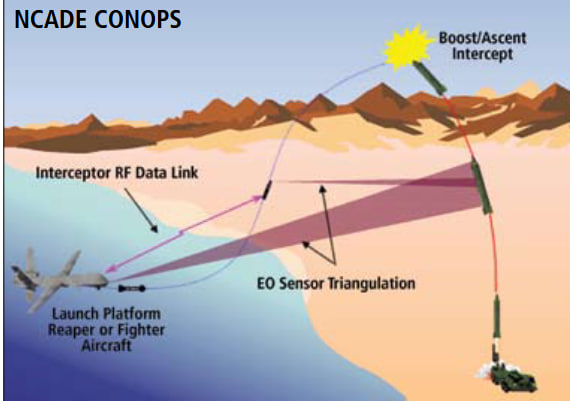

The Network Centric Airborne Defense Element (NCADE) program, launched in the 2000s, envisioned intercepting short- and medium-range ballistic missiles during their boost and ascent phases. To achieve this, the U.S. pursued a low-cost, air-launched solution developed jointly by Raytheon and Aerojet.

A key aspect of the program was the use of components from existing air-to-air missiles, specifically the AIM-120. At minimum, this included its aerodynamic design, interface, and flight control system.

Thanks to its compact size and design, the new interceptor missile was intended to be launched from almost any U.S. fighter aircraft, including the F-16, F-15, F/A-18, F-22, and F-35, as well as the MQ-9 Reaper UAV. This would have offered significant operational flexibility without requiring additional aircraft modifications.

The project progressed to component testing. In 2007, two short-range AIM-9X air-to-air missiles equipped with the new NCADE seeker successfully intercepted a ballistic missile. The launch platform used during the test was an F-16, demonstrating the feasibility of the concept.

According to information released at the time, for a fully developed NCADE interceptor to successfully engage a ballistic missile, the launch aircraft needed to be within 160 kilometers of the missile’s launch site. If that number sounds overly optimistic, it was. By 2012, revised calculations showed the required distance had dropped to just 50 kilometers.

Moreover, the U.S. National Research Council’s Committee on an Assessment of Concepts and Systems for U.S. Boost-Phase Missile Defense concluded that ballistic missiles begin their boost phase at altitudes too high for reliable interception. This significantly limits the time window for engagement and increases the vulnerability of the fighter aircraft acting as the launch platform.

In other words, the program yielded a highly niche interceptor, and its shortcomings stemmed directly from its core concept. Intercepting a ballistic missile during its boost phase from a fighter jet proved far less practical than using conventional ground-based air defense systems such as the Patriot PAC-3 MSE.

Given this in-depth analysis, it is no surprise that the NCADE program was ultimately canceled. Among the reasons cited for its termination were a lack of development progress and diminishing interest from defense planners.

In retrospect, NCADE was an intriguing concept, but one fundamentally aimed in the wrong direction from the start. This is why the current AIM-174B program may prove more effective at intercepting ballistic and hypersonic threats, as it is based on a more traditional and viable operational framework.

Read more: Testing Begins for New Viper Shield EW System for F-16V, Poised to Act as "Electronic Shield" in the Sky