Installing anti-tank missile launchers on unmanned aerial vehicles is uncharted waters in weapon development, with only a few solutions presented on the world market just recently. It allows small units to acquire their own "attack helicopter" and quickly deploy a no-go area for enemy tanks at a designated location, it increases the attack range of anti-tank weapons and keeps their operators safe from backfire.

The idea found its iteration in russia as well. In particular, there is the Termit unmanned helicopter that allegedly entered mass production over the past year. However, as they realized how long it would take until the first working units reached the frontlines, the russians started to locally experiment with makeshift solutions with already familiar missile systems. Such as mounting a 9K111 Fagot on a heavy-lift copter drone.

Read more: russian Propagandists Suggest belarusian Hunter UAV Could Be a Potential 'Pair' for the Termit UAV

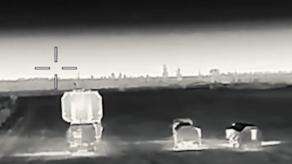

The video shows a successful takeoff with a 34-kg loaded launcher (though here the system lacks the swivel, thus the overall mass is a bit lower) and even the firing of the anti-tank missile. Yet, the real problem here is not to do all that but actually hit the target.

Landing a hit requires guiding the missile. For that, the Fagot operator needs to keep the target within the crosshairs, while a complex process is happening on the outside. The targeting device called 9Sh119M1 receives the emission of the lamp implanted on the aft side of the missile and sends command signals via wires. These commands adjust the missile's pitch and yaw proportionately to the missile's deviation from the aiming point.

When an ordinary launcher is deployed, the operator controls the aiming point with a set of levers. When mounted on a drone, keeping the aim on target is practically very difficult. The simplest way to implement this would be to keep the target in the center of the camera view but the copter sways in both horizontal plane and altitude. Moreover, the controls do not allow for turning mere fractions of degrees, a precision important for landing an accurate hit.

If the system does have additional servomotors, like in the Ukrainian Stuhna-P/Skif ATGM (which is not likely), the situation won't change much: the drone is still a very unstable platform for manual control of a flying missile. The only attachment that can compensate for this shortcoming is a gyroscopic stabilizer with all associated design complexities.

Therefore, the overall assessment is that such makeshift flying ATGMs won't revolutionize the domain and won't even prove effective on the frontline. At least effective enough for the manufacturer to think of mass-producing these.

At the same time, the attempt to use Fagot as the basis for this weapon is understandable: russia simply has no ATGMs with alternative guidance systems that could be combined with an aerial drone.

Because the best for this purpose is a missile with semi-active laser homing, it's when the target is designated by a laser beam from a stable ground. This is the kind of guidance implemented, for example, in the British Jackal drone with Martlet (Lightweight Multirole Missile — LMM) missiles. A similar solution the russians are trying to realize in the aforementioned Termit uncrewed helicopter.

Another approach is to use active radar homing missiles, such as Brimstone. They don't rely on external guidance and find the target on their own. Alternatively, there's also thermal homing, as in the Javelin or latest versions of Spike; the latter might even be the best pair to an aerial drone because the operator can guide the missile toward its target by looking through the camera installed on the missile itself.

The cheapest, though, is semi-active laser guidance. However, Moscow hasn't gone further than announcing the beginning of production of S-8L, a russian analog of APKWS. Therefore, the troops out in the field have to go creative.

Read more: Some Details of Joint Production of Drones Between Ukraine, the UK Revealed