The russian federation in its pursuit of hypersonic missiles significantly relies on the legacy of the Soviet Union and its technologies developed in the 1980s. Among these projects, aimed at achieving hypersonic speeds or surpassing them, the Kh-90 stands out.

Considering that such missiles as the Kalibr, the R-500 for the Iskander SRBM system, and even the Kh-47 Kinzhal are also Soviet projects originating in the 1980s, the Kremlin may be planning to add the Kh-90 to its arsenal as well, sooner or later.

Read more: How russian 3M22 Zircon Reached Hypersonic Yet Failed to Accomplish the Very Task it was Created For

The history of the Kh-90 missile is connected to two major players in the domain, one being the MKB Raduga design bureau, the same company that developed the notorious "almost hypersonic" Kh-15 and most of the missiles that russians now use against Ukraine: Kh-22, Kh-32, Kh-59, Kh-555, Kh-101. The second one is the NPO Mashinostroyeniya that was supposed to be responsible for production. Now the company is making Oniks and Zircon missiles, among other things.

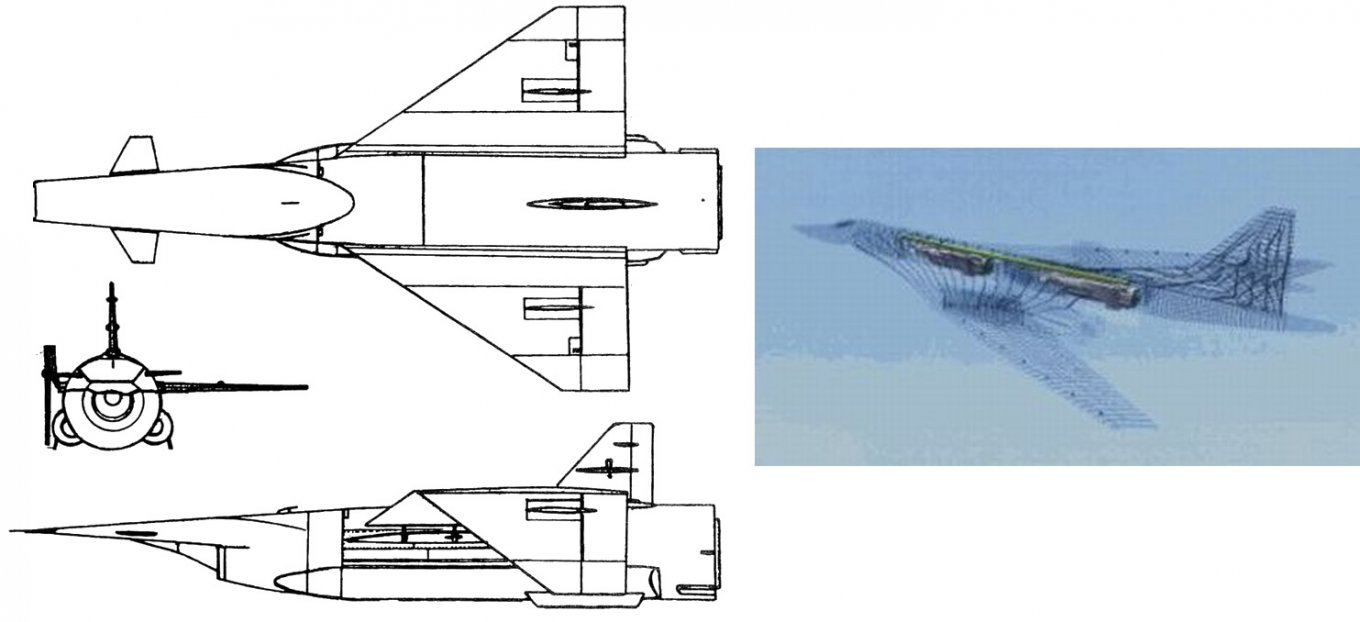

The origins of the Kh-90 can be traced back to the early 1980s within the Soviet Union, where it was conceived under the codename "B-239" as a successor to the Kh-55 subsonic cruise missile. Envisioned as a ramjet-powered missile capable of achieving speeds between Mach 4.5 and 6 (data varies in sources), the Kh-90 aimed to penetrate "existing and future" air defense systems. The expected operational range was 3,000 kilometers.

The role of the Kh-90's carrier was supposed to belong to the Tu-160 strategic bomber, which by that time had already performed its maiden flight in 1981. The two weapon bays on the aircraft would only house one missile each, so the small capacity was compensated by the missile's unique feature of housing two warheads within its compact frame to engage multiple targets. A similar solution was later used by russians in their recently presented new version of the Kh-101.

The missile was 11 meters long, the folding wings spanned for 7 meters, the planned weight was 15 tons. The guidance, on top of the standard inertial system, was complemented by a Soviet variant of DSMAC, the difference though is that it compared radar reflections, not optical images, with a reference stored in memory. Most likely, it was the SNRK Kadr which stands for "system of navigation by radar maps," originally developed for the 3M-25 Meteorit (P-750) cruise missile that was never finished.

The missile's launch sequence required a release at an altitude of at least 7 km, followed by ignition of the solid fuel booster to attain the necessary velocity for the hypersonic ramjet engine to start working. Bench tests of the engine were completed around 1988, meanwhile the the tests of the Kh-90 prototypes were underway, the first ones having started a year earlier at the Engels Air Base.

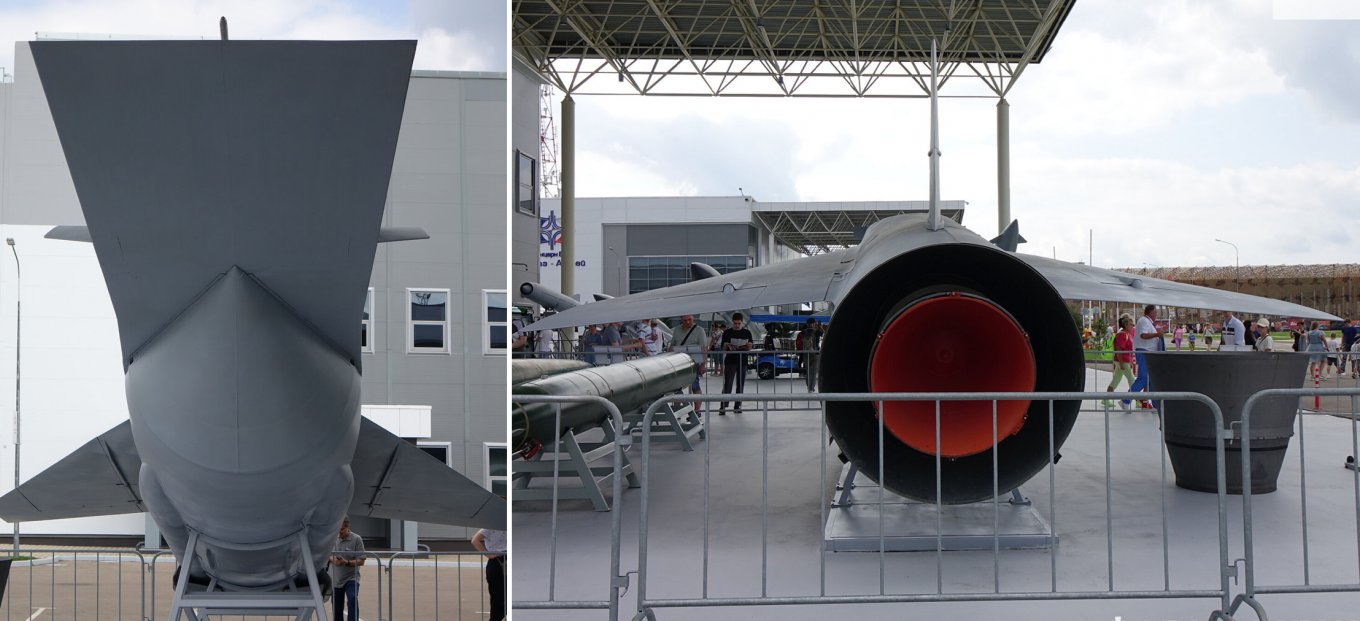

The developments were promising but the USSR had already begun to collapse so they became no longer relevant, the works lasted until a proclaimed closure of the program in 1992. Against the backdrop of the search for funding, the MKB Raduga openly demonstrated one of the Kh-90 prototypes or its dummy model at the MAKS-1995 exhibition. But they labeled it "GELA," an acronym for "hypersonic experimental aircraft."

At this point, the traces of this development are lost, apart from the fact that the dummy was later put on display at the company's exhibition space.

But in 2012, rather unexpectedly, an insider from the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI), the leading russian research center in the domain, leaked some information to the russian media. The source stated that the first launches of the Kh-90 were already planned at the 929th Test Center of the russian Ministry of Defense in Akhtubinsk, but the work was "suspended" for two years.

In response, MKB Raduga commented that the company had not been working in this direction for 10 years, that is, since 2002, which also does not align with the information regarding the closure of the project in the 1990s. Afterward, the missile project was forgotten until the "GELA" was once again demonstrated at the Army-2019 exhibition, although the only ones who paid any interest to the exhibit were connoisseurs of military history.

Then in 2023, russian military-themed media reignited the topic with multiple articles about the missile displayed at the very same booth. According to those articles, the works on the project were resumed in 2009 with the aim of "obtaining the latest strategic attack weapons."

Therefore, taking into account that the russian federation has solved the main problem of creating such missiles — created its own supersonic combustion ramjet engine — the re-emergence of the Kh-90 as a working product appears to be a realistic scenario.

Though it will most likely prove as helpless as the hypersonic Zircon missile that failed to accomplish the main task it was created for. And the explanation for such a situation in the russian missile industry is quite banal, in fact. Hypersonic missiles in the USSR were designed in the 1980s and were supposed to enter service in the 1990s or 2000s, now these devices lag behind the capabilities of Western anti-missile defenses by 20 years.

Read more: Why Western Tank is No Jack of All Trades in Assault But a Very Specialized Vehicle