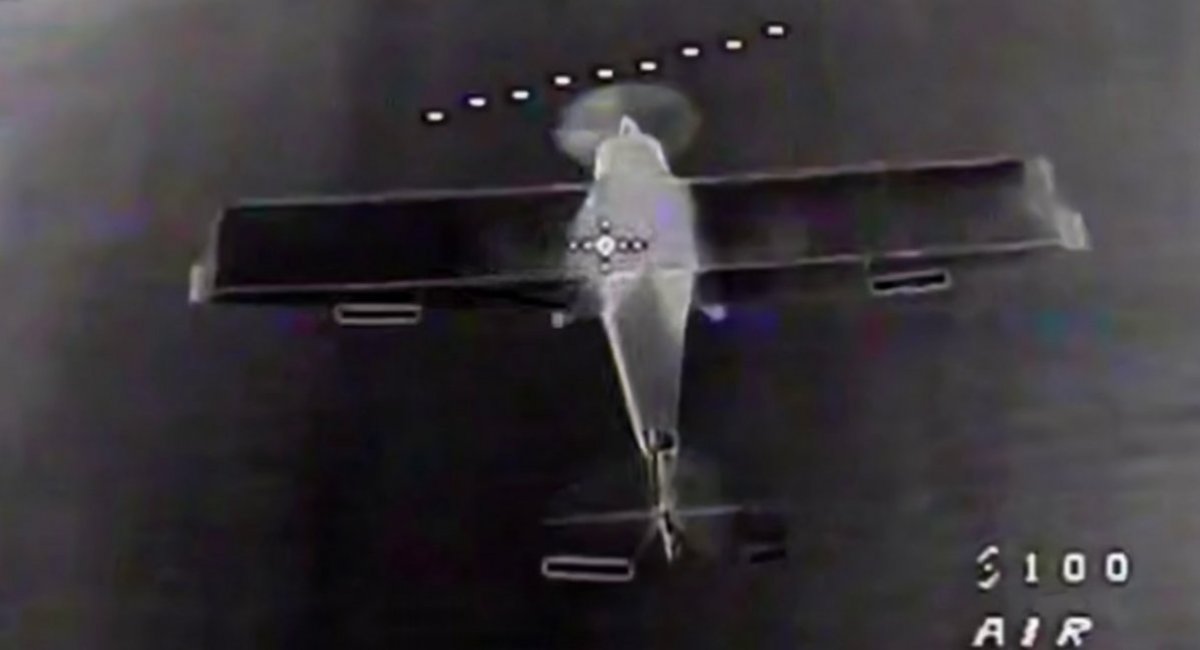

russian units have begun systematically intercepting Ukrainian long-range strike drones using purpose-built anti-air UAVs, a development that is dangerous yet, given battlefield learning on both sides, not entirely surprising. According to field reports, some of the most popular deep-strike platforms, such as the FP-1, Liutyi series, and E-300 variant based on a light-aircraft frame, have already come under attack. The shift shows how adversaries rapidly adapt successful tactics they observe in combat, turning Ukrainian innovations back against their creators.

Tactically, russian operators appear to be using swarm and intercept doctrines: multiple interceptor drones are launched against a single target, sometimes pursuing from behind and other times flown to meet the incoming strike head-on.

Read more: Ukrainian Phoenix Border Guard Unit Eliminates around 50 russian Soldiers in Series of Precision Drone Strikes (Video)

This paired approach increases the probability of a kill, complicates evasive maneuvers for the attacking aircraft, and forces attackers to spend more time and resources on each strike mission. In effect, the enemy is attempting to recreate Ukraine's own practice of using aerial assets to defeat russian loitering munitions and the Shahed-type systems.

That mirroring is predictable: Ukrainian forces for months have adapted small anti-air drones to shoot down russian Geran-type and Shahed UAVs, so it was only a matter of time before similar capabilities reappeared on the other side.

What is worrying is the speed and focus of that adaptation. When the opponent develops a credible local counter to low-altitude, low-cost strike drones, entire portions of the attacker's operational playbook, particularly those relying on massed, inexpensive systems, suddenly become more costly and less certain.

The rise of drone interceptors raises hard questions about how to preserve the strategic value of long-range strike UAVs. One obvious alternative is to shift to higher flight profiles, but raising altitude brings trade-offs: higher-flying drones become easier for ground- and air-based sensors to detect, track, and engage with traditional air defenses. Moreover, higher-altitude profiles can demand different airframes and propulsion systems, driving up unit cost and undermining the cheap, expendable mass that makes deep-strike drones effective in the first place.

More technically nuanced countermeasures are already being trialed. Reconnaissance UAVs can pair with strike platforms, streaming camera feeds and sensor data to guide last-second evasive maneuvers and warn of inbound interceptors. Electronic warfare payloads, decoys, and simple AI-driven evasive algorithms can complicate an interceptor's targeting solution. Yet integrating such systems into long-range, low-cost strike drones is a difficult engineering challenge: each new sensor or countermeasure increases weight, cost, and complexity and may reduce range or endurance.

It's important to note that not all strike options are vulnerable to small anti-air drones. Cruise and ballistic missiles remain largely immune to this class of interceptor, but they are far more expensive to produce and deploy. That price gap is precisely why drones fill a niche: they make deep strikes affordable at scale, allowing attritional pressure on infrastructure and logistics that would be prohibitively costly with missiles alone. Any solution must therefore preserve the cost-effectiveness that underpins drone massing while improving survivability.

Read more: Ukraine Seals Deal With LeVanta Tech Inc. That Could Sink russia's Entire Black Sea Fleet