For the russian invasion forces, the Shahed-136/131 loitering munitions at this point have become not just the most numerous weapon for long-range strikes on Ukraine. When combined, one wave of these killer drones take many times more explosives into Ukrainian territory than missiles can ever hope to carry.

And despite the grim forecasts that russia may soon be able to launch as many as 1,000 drones on a daily basis — even though the Shahed-136 production rate currently stands at only 90 drones a day — finding no evidence, the general line of though in Kremlin to wear Ukraine down with relentless Shahed attacks is quite obvious. The question is what Ukraine can do to thwart this plan of russia's.

Read more: Anti-Aircraft FPV Drones Have Potential Greater Than Traditional Air Defense Missiles

After all, it's the first time that the principle — where using anti-aircraft artillery and even missiles to intercept air threats was cheaper and produced faster than the target itself, be it an aircraft or a helicopter — was turned upside down at such a scale. This is despite the fact anti-air missiles have traditionally been more affordable than, say, cruise or ballistic missiles.

The Shaheds, on the other hand, are mass-produced by russia at a fairly low cost of $193,000 as of 2023 data (though not $20,000–$40,000, as once believed). Still, they are cheaper than interceptors due to their very short technological cycle. They don't require rare components, complex production, or unique specialists. That's why russians churn out about a hundred of them daily, and only a few actual missiles in the meanwhile.

Now, anti-aircraft drones. The technology has already successfully proven effective against reconnaissance UAVs, and it's something Ukraine can mass-produce on its own, from available components and on a relatively small industrial foundation. Their manufacturing cost is far cheaper than that of russian Shaheds, although still higher than ordinary FPV drones.

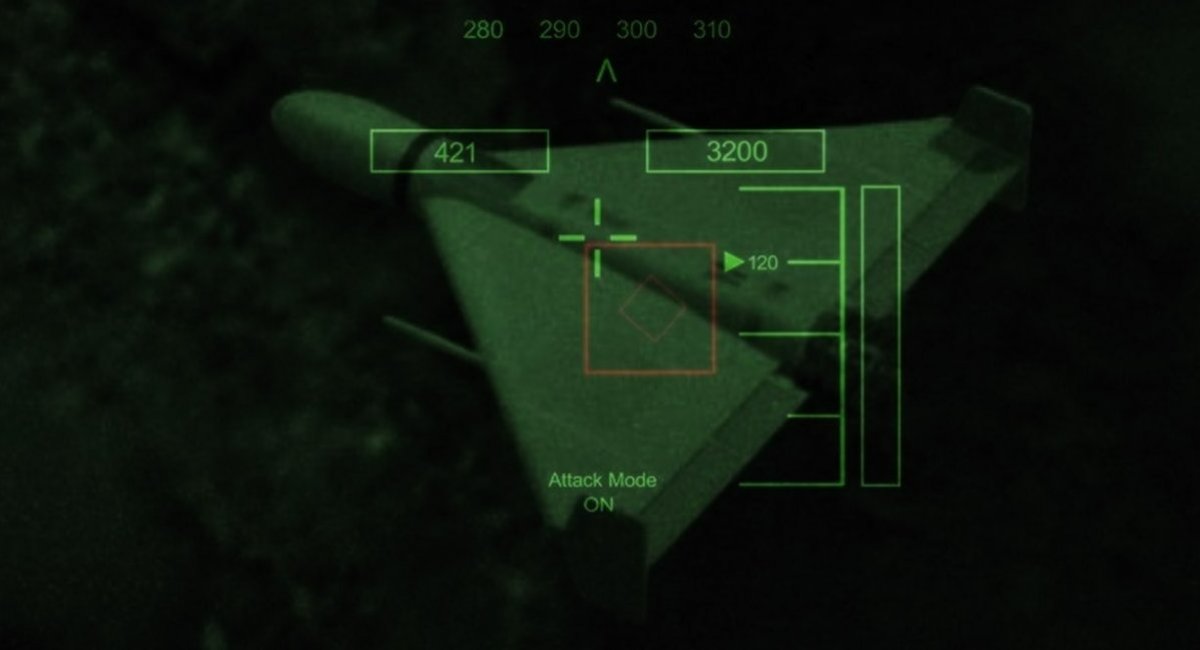

This can be explained by the need to install expensive night vision cameras to catch Shahed-136 which are launched usually in dark hours. Secondly, in order to be effective, anti-aircraft drones need to get rid of reliance on the operator's personal skill to hit the target — that would necessitate the so-called "machine vision," i.e. a visual homing system.

Possible alternatives may be other systems that help avoid a situation where one operator controls one drone to hit one target, without the right for failure and a second chance. This calls for developing swarm use techniques and automated guidance, thus solving problems with the drone's single-channel nature and opens the possibility of engaging several threats simultaneously.

For example, one can look towards the guidance systems employed on air-to-air or surface-to-air missiles. Among them, the first and cheapest choice is the command guidance, where the interceptor must fly to a specific coordinate point, calculated on the ground as the meeting point with the target.

Then, there's semi-active laser guidance, where the effector homes on a target illuminated by a laser from the ground or a friendly aircraft. Perhaps even the relatively cheap acoustic guidance can work, which requires doing something with the noise issues. Variants for visual recognition are on the table as well — those identify the target by analyzing the image from the camera, aka the machine vision mentioned earlier.

Once the homing method is selected, Ukrianians will then have to deal with a whole bunch of problems with system deployment time, sometimes done already in the air, with reaching the appropriate speeds and altitudes to catch the threat. Another but not the last, it must be ready for use at any time of the day, any weather and visibility. Because, after all, Shaheds can fly in rain, snow, and fog.

These challenges must be solved all at once, since the range of an anti-aircraft drone when launched from the ground is very limited, while the time required to engage the threat is by far longer than any conventional surface-to-air missile can last. The drone will need a proximity fuze, not an impact one to significantly increase the chances of destroying the target upon contact.

To summarize, even with all the benefits it provides like affordability and mass production, making the anti-aircraft drone an effective and efficient counter to Shahed-136/131 is a much more complex task than simply using ready-made FPV drones, already used with much success against russian scout UAVs.

The very same hurdles ultimately forced Raytheon to convert the relatively simple and cheap propeller-driven Coyote into the sophisticated Coyote 2C jet drone with a semi-active radar homing head. Even then, such drones are still cheaper and simpler than traditional anti-aircraft missiles.

Read more: First-Ever Helicopter Launch: Raytheon’s Coyote LE SR Drone Has Completed Its First Helicopter Launch