France has yet to actively push the idea of replacing the U.S. nuclear umbrella with its own deterrent force, but the concept continues to surface in strategic discussions, particularly as Europe rethinks its security architecture amid rising threats. A key question lies at the heart of the debate: does Paris have the political will, psychological readiness, and nuclear capability to protect Europe?

This topic is the focus of a recent analysis published by War on the Rocks, which essentially argues the following: for France to offer a credible nuclear umbrella to Europe, it must be willing to use nuclear weapons, even to the extent of destroying Moscow. But is France truly prepared to make such a commitment?

Read more: When the U.S. Had 800-Kilometer Nuclear Anti-Air Missiles Against Tu-95 Bombers — and Why They’re Gone Now

France became a nuclear power in 1968 under President Charles de Gaulle, who formulated a core principle of French nuclear doctrine known as dissuasion du faible au fort — the "ambiguity of deterrence." Under this concept, adversaries should never be certain how far France is willing to go in employing nuclear weapons. Strategic ambiguity is intended to enhance deterrence by keeping potential enemies guessing.

But when it comes to extending that deterrence beyond France’s borders, to include European allies, ambiguity may not be enough. The psychological threshold for launching a nuclear strike in defense of another nation, even a close partner, is vastly higher than defending one’s own territory. And this is precisely where doubts begin to surface.

By the 1970s, French military planners had begun to adopt a more assertive posture, declaring that France’s nuclear deterrent extended beyond its national territory. However, this doctrine did not last long. In the early 1980s, with the election of François Mitterrand as president, French nuclear policy took a more passive turn.

Mitterrand, who led France from 1981 to 1995, is often seen as having deliberately avoided confronting the question of nuclear deterrence. As observers have noted, he seemed to hope the issue would resolve itself. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Warsaw Pact dissolved, and the Cold War formally ended, France responded by scaling back its nuclear posture, even initiating steps toward partial disarmament.

A case in point is the retirement of the Hadès short-range ballistic missile system, developed in the 1980s to carry nuclear warheads. Often described as the French equivalent of russia’s Iskander system, Hadès was scrapped before it could become a permanent fixture of France’s arsenal.

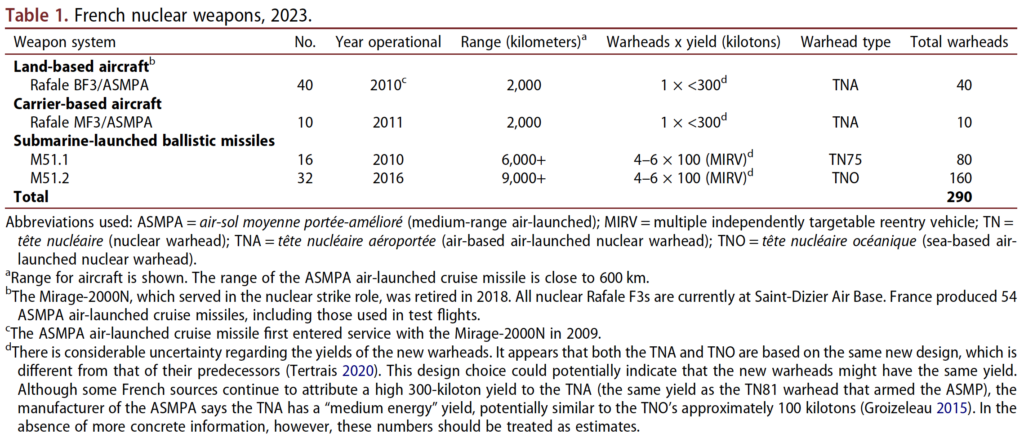

Today, France maintains a robust nuclear dyad, composed of air- and sea-based delivery platforms. But this leads to a deeper strategic question: would Paris actually be willing to press the nuclear button if circumstances demanded it? And is the current French arsenal truly sufficient to inflict unacceptable damage on a major adversary — such as russia?

After all, the so-called "Moscow criterion", the readiness to strike russia with nuclear weapons and impose crippling losses, has long been a central tenet of the United Kingdom’s deterrence posture. During the Cold War, France itself possessed such a sizable nuclear arsenal that no one doubted its ability or will to impose catastrophic consequences on any aggressor.

In light of these dilemmas, perhaps the more realistic course is not for France to offer an abstract “nuclear umbrella” for all of Europe, but rather to fully integrate into NATO’s nuclear planning structures. Doing so would allow Paris to contribute to collective deterrence without bearing the burden of unilateral nuclear guarantees.

Read more: France Conducts Poker-2025 Nuclear Exercise for All to See