When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Ukraine inherited the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal, estimated at between 1,500 and 1,900 strategic warheads. However, just five years later, on June 2, 1996, the last batch of nuclear weapons was shipped to russia, then by 2001, all 176 underground launch facilities had been decommissioned.

The prevailing sentiment in Washington at the time was that russia alone should succeed the Soviet Union as a nuclear power. Of course, a significant role in Ukraine’s disarmament process belongs to the so-called Budapest Memorandum.

Read more: Nuclear Strike Rehearsal: russia Launched RS-26 Rubezh or a Different ICBM on Ukraine, Consequences Are Null

What Ukraine Signed Up For

Let us recall that the full name of the document is: Memorandum on Security Assurances in connection with Ukraine's accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. It was concluded on December 5, 1994, between Ukraine, russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America due to Ukraine's acquisition of non-nuclear status. On the same day, Ukraine also joined the mentioned Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The memorandum contained six fundamental commitments regarding guarantees of security and territorial integrity of Ukraine provided by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the russian federation.

In particular, the parties pledged to respect the existing borders of Ukraine, not to use either military force or economic pressure on its sovereignty, and to provide comprehensive assistance if the country becomes a victim of armed aggression. There's a separate emphasis on refraining from using nuclear weapons against Ukraine.

As you may notice, these commitments were described as "security assurances" from their guarantors, and since the document didn't undergo the ratification procedure, it has no legal binding force, thus the obligations of the participating states are reduced to purely political ones.

From the very beginning, russia considered the Budapest Memorandum as a way to legitimize the nuclear disarmament of Ukraine but primarily because it considered the young breakaway state a sphere of its influence. Afterward, the Kremlin consistently interpreted the clauses of the agreement as it saw fit.

Such as, when the russian troops known as the "little green men" occupied Crimea, the response from the USA, Canada, Great Britain, and other countries was to declare this a direct violation of the Memorandum. To which Putin replied that after the Revolution of Dignity (allegedly instigated by Washington), a "coup d'état" inKyiv led to the creation of a new state in Ukraine that russia had no obligations to and signed no papers with.

Phantom Pains Over a Phantom Choice

For better or worse, there was no alternative to signing the Budapest Memorandum at the time. This was prompted by both the societal consensus and the international status of Ukraine as a young state with a political course unpredictable to its neighbors and potential partners.

The nuclear disarmament of Ukraine had an impact not only on the country's security sector but also gave it an invitation to take its place in the international community among the world's democracies and made it a welcome associate for various intergovernmental programs.

On the flip side, the security aspect of the Memorandum was clearly overestimated. Although the document made a significant contribution to the formation of foreign policy around Ukraine and at some point even gave a start to its integration into pan-European financial and defense organizations (read: NATO). However, Putin’s bet on the inertia of the signatory states if he were to violate the Memorandum bore fruit, which began to ripen long before the full-scale invasion in 2022.

Compensation for the Loss

In the current realities, Ukraine must look for new ways to ensure its own national security. Some voices inside the nation call for the revival of Ukraine’s nuclear potential, and we must admit that there is some reason behind these calls.

For a reminder, it was russia's violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty that gave grounds for restarting the missile program in the United States.

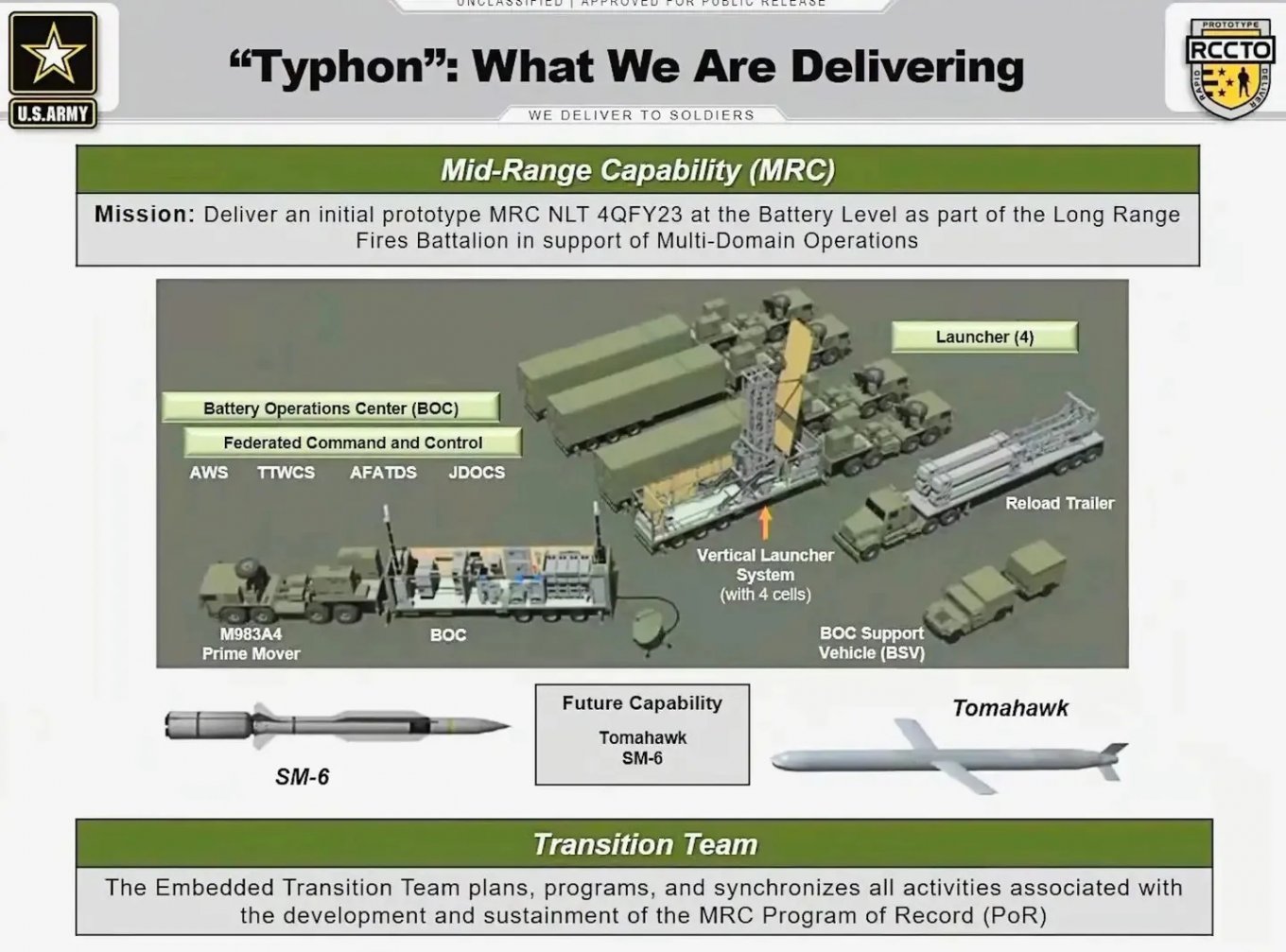

This led, in particular, to the emergence of systems like the ground-based Typhon system that deploys the Tomahawk, the multirole SM-6 capable of both intercepting air targets and attacking objects on the ground, and the LRHW — Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon.

It is worth noting that the transfer of the Typhon system could have been implied under the "non-nuclear deterrence package" against russia, an essential part of President Volodymyr Zelenskyi's "Victory Plan" presented earlier this October.

But here we must note that there are more realistic ways to achieve the desired effect while avoiding the political toxicity of the decision to restore Ukraine's nuclear status in the international arena. First such step is developing domestic long-range weapons programs that can hold the enemy's military-industrial complex at gunpoint using completely conventional methods.

Speaking of domestic projects, Zelenskyi recently announced that Ukraine is already working on four types of indigenous missiles and that their testing is currently underway. No less important, still, is to seek supplies of long-range weapons from international partners: the same Typhon system or the air-based AGM-158 JASSM for F-16s should be persistently negotiated. This is the least the guarantors of the Budapest Memorandum can do after one of them — russia — has broken the promise.

Read more: NATO Responds to Ukraine's Call For 20 Air Defense Systems in the Wake of Winter